The famously anti-communist Richard Nixon went to China. Bill Clinton, the champion of single-payer health care, declared the era of big government over. Could Donald Trump, who once described himself as the “king of debt,” be the first president in decades to achieve fiscal balance?

“In the near future, I want to do what has not been done in 24 years: balance the federal budget,” Trump said Tuesday at his address to Congress. “We’re going to balance it.”

A bold goal with a vague timeline is hardly the makings of a successful policy venture, but it’s given us a benchmark. So how will the Trump administration and the Republican Congress erase last year’s $1.8 trillion shortfall, as measured by the Congressional Budget Office? Trump’s speech offered few concrete ideas for cutting spending and raising revenue.

The president mentioned attention-grabbing examples of supposedly ridiculous foreign aid (“$8 million to promote LGBTQI+ in the African nation of Lesotho” which may refer to money for treatment for HIV-positive people in that country) and vague claims of fraudulent payments and unnecessary bureaucracy, inspired by Elon Musk’s DOGE hack of the executive branch that has identified but cannot eliminate congressionally-appropriated money. The specific ways Trump mentioned raising revenue amounted to a plan to offer visas to wealthy foreigners for the price of $5 million, the receipts from more tariffs, and a fuzzy sense that a coming economic boom brought by extending tax cuts and cutting back on government regulations will refill the federal coffers.

But the White House’s guidance on how to achieve a balanced budget has not yet extended far beyond this scattershot of outrageous examples of abuse and ideas for jump-starting the economy. (Except one directive: Don’t touch entitlement spending, which doesn’t seem likely to help Trump achieve his goal.) In order to reach this ambitious objective and deliver Trump a win, GOP lawmakers are otherwise on their own to identify where else to cut and make up the deficit. When it comes to the details, White House is taking a “hands-off” approach, as Republicans on the Hill have put it.

All those are big reasons budget hawks are skeptical of Trump’s boast.

“Trump and Elon Musk, they’re setting up all these unrealistic expectations amongst MAGA followers that their actions are solving the deficit crisis, and it’s not,” said Chris Edwards, a scholar at the libertarian Cato Institute who edits DownsizingGovernment.org.

So while the president has pledged an incredible turnaround in the government’s fiscal situation—all while demanding it be done as one “big, beautiful bill”—it’s now up to Congress to codify the Trump-Musk cuts into law. That process is already underway and unlike Musk’s shock-and-awe march through the executive branch, what happens on Capitol Hill promises to be a slog throughout.

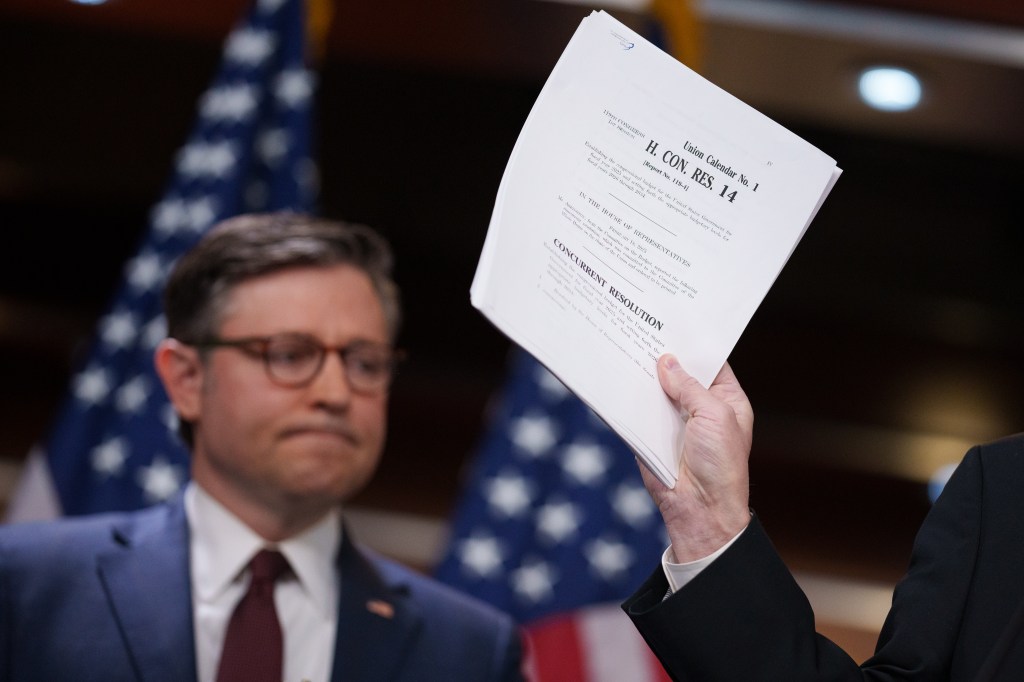

It starts with the budget framework, which the House Republican majority passed last month and which instructs Congress about how to go about appropriating money and setting tax policy. The resolution would require $4.5 billion in tax cuts and $2 trillion in spending cuts over the next decade, and only barely passed after some last-minute strong-arming of fiscal hawks in the GOP conference.

It’s a long journey from here to anything resembling a cut in spending. The Senate will have to consider, amend, and adopt the House’s budget, a process it won’t kick off until at least the end of March. And it will take time for Republicans on that side of the Capitol to land on a version of the House resolution that can pass the Senate and eventually be reconciled with the House version. (The Republican majority in the Senate already adopted its own separate budget framework, smaller and more narrowly focused on funding border security and national defense, following Majority Leader John Thune’s preference for two separate funding bills.)

If and when the House and Senate eventually agree on a budget resolution, then the work of the authorizing committees, appropriators, and tax-policy writers truly begins. Committees will hold hearings, line items will be discussed, appropriations and tax policy will be drafted, all of it according to the rules set out by the budget resolution. Oh, and somewhere along the line, the Trump administration itself will present a budget to Congress, which may induce further rewrites and amendments. A final bill may not be ready until the fall.

(All of this ignores the ongoing parallel process whereby leaders in both houses and parties are hammering out a deal for another stopgap temporary funding resolution once the existing funding mechanism expires next week on March 14. That would avoid a government shutdown and give Republicans in Congress some breathing room to continue the work on an actual budget for the next fiscal year. And don’t get me started on the likelihood of hitting the debt limit this summer.)

If this all sounds complex, that’s because it is complex. Trying to jump through procedural hoops and requirements to get to a budget that funds the priorities of the Trump administration, particularly on securing the southern border and restricting immigration, will not be an easy task. Republicans on the Hill are sounding optimistic that this big, beautiful bill can become law. “We’ve climbed harder hills just within the past couple weeks,” Rep. Blake Moore of Utah recently told the Washington Post.

But there’s still the pesky task of actually passing the thing, and a narrow majority for the GOP in the House leaves practically no room for losing members of their conference.

Yet there are dozens of places—from preferred pork projects that might be on the chopping block to impasses over the cap on the deduction for state and local taxes—where the incentives for individual Republican members may be in conflict with passing a bill that gets close to the promised $2 trillion in cuts. There are some major budgeting conundrums, such as the Congressional Budget Office’s recent analysis that the Republicans’ proposed spending reductions can’t be achieved without making significant cuts to Medicaid or Medicare. Indeed, as Jessica Reidl has noted, the proposed cuts to mandatory entitlement programs are likely to face opposition even within the GOP ranks once the details are known. And there are still a few true-believing fiscal hawks who are already signalling they can’t back a bill that won’t make even bigger cuts.

Contrary to Trump’s self-assured attitude that achieving something like a balanced budget or even a significantly narrower budget deficit is simple, this is quite difficult to do even in great economic circumstances. The last surplus was in 2001, ending a four-year run when a Republican Congress and a Democratic president, Bill Clinton, spent less than they took in. Clinton and congressional Republicans achieved this by reducing spending, following financing rules requiring offsetting increases in mandatory entitlement spending with cuts elsewhere, and benefiting from increased tax receipts from high-income earners thriving in a booming economy.

The secret sauce appeared to be a left-of-center president who wanted to show that government could work and a right-of-center legislature that pushed for fiscal responsibility, all against the backdrop of a thriving national economy.

But a quarter-century later, despite Republican control of Washington, the building blocks for fiscal sanity seem to be missing. The economic outlook is mixed. The Congress is too evenly split. And despite having cut-hungry advisers like Musk and White House budget director Russell Vought in charge, Trump’s fill-in-the-details-later approach suggests he’s prioritizing the appearance of spending cuts over real, long-term, and effective shrinking of the federal government.

“People talk a lot about the different structural reforms we could do, balanced budget requirements and all this sort of stuff, that would all be fine, but really, you just need a president who is committed and who puts it as a top priority,” Edwards said.