Over the last few days, we have noted some cracks/leaks (choose your analogy) appearing in the plumbing of the market.

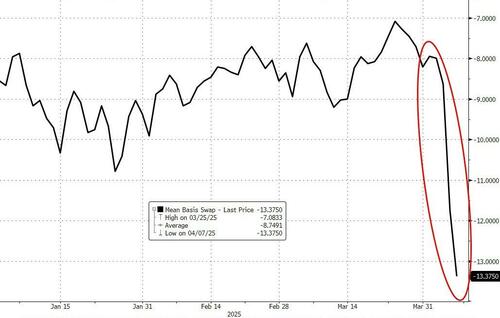

Cross-currency basis swap spreads started to blow out…

…suggesting a huge and sudden demand for US dollars.

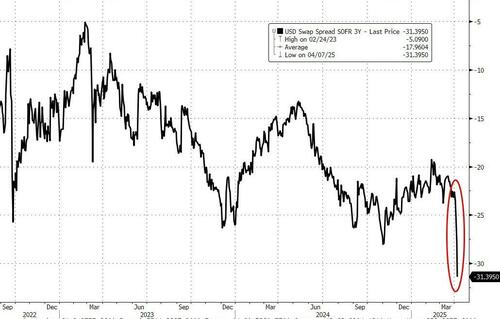

Additionally, SOFR swap spreads hit record wides…

…suggesting some credit risk fears building in the markets.

These two events stabilized a little today as markets rallied, but it got us thinking if there is something else going on, and that is where Robert McCauley comes in, wirting an op-ed for The Financial Times explaining why doubts over the Fed’s dollar swap lines are such a big deal.

Kindleberger’s Trap is the danger that a fading hegemon lacks the ability but the ascendant one lacks the will to supply the world economy with vital public goods — such as a reserve currency. In the 1930s, the Bank of England lacked the ability to continue to serve as international lender of last resort, and the ascendant Federal Reserve lacked the will to do so.

As a result, crisis spread from Austria to Germany and Britain and ultimately reached the US, turning the post-1929 slump into an era-defining economic collapse. The Kindleberger Trap led to “the world in depression”, as Charles Kindleberger titled his seminal book.

This is why worries over whether the Federal Reserve will continue to supply dollars to overseas central banks at times of financial strife are such a big deal. As Reuters reported last month:

Some European central banking and supervisory officials are questioning whether they can still rely on the U.S. Federal Reserve to provide dollar funding in times of market stress, six people familiar with the matter said, casting some doubt over what has been a bedrock of financial stability.

The sources told Reuters they consider it highly unlikely the Fed would not honour its funding backstops — and the U.S. central bank itself has given no signals to suggest that.

But the European officials have held informal discussions about this possibility — which Reuters is reporting for the first time — because their trust in the United States government has been shaken by some of the Trump administration’s policies.

These concerns are warranted, both in light of the Trump administration’s distaste for America’s traditional alliances and the centrality of the Fed’s swap lines to global financial stability.

As Deutsche Bank’s chief FX strategist George Saravelos highlighted in a recent report on the topic, doubts over the Fed’s willingness or ability to step up when needed on is a “nuclear button” for the dollar’s future:

Ultimately, a withdrawal of the Fed as the international lender of last resort is equivalent to a suspension of the dollar’s role as the safest of global currencies. Doubts about a commitment from the Fed to maintain dollar liquidity — especially against major allies — would accelerate efforts by other countries to reduce their dependence on the US financial system. It would ultimately lead to lower foreign ownership of US assets and a broad-based weakening of the dollar’s role in the global financial system.

In the 2008 and 2020 dollar panics, the Fed wisely told 14 central banks that the buck starts here. Through official swap lines the Fed could extend its credit to each central bank against domestic currency as collateral.

Each central bank could in turn lend the dollars to banks in its market against domestic collateral.

Reaching outstandings as high as $598bn in 2008 and $449bn in 2020, the swaps succeeded in stabilising global dollar markets. The amounts were not small, but offshore dollar lending — both on- and off-balance sheet — is measured in the tens of trillions of dollars. Thus, with pennies on the dollar lent and repaid with interest, co-operating central banks calmed these potentially destructive dollar panics.

The US also won from the Fed’s international provision of dollars. Crucially, the swaps reversed market-driven interest rate hikes on Libor-priced US corporate loans and mortgages, which in turn would have hammered US jobs and consumption. As Saravelos pointed out:

Had the Fed not stepped in during the 2008/9 financial crisis and Covid pandemic, the reserves of foreign central banks and international lenders like the IMF would unlikely have been sufficient to meet global dollar demand, leading to an even greater surge in dollar borrowing costs than occurred at the time, defaults, and potentially systemic implications for the global financial system.

What if a crisis like 2008 or 2020 happens and the Fed does not swap dollars? Central bankers would not be doing their jobs if they weren’t asking this question.

If it came to such a scenario of “politicise[d] . . . recourse to the dollar swap lines,“ the Fed would have the ability but not the will, as in 1931. Any other single central bank might have the will but not the ability.

However, central bankers could form a dollar coalition of the willing.

The central fact is that the 14 central banks that had standing and temporary Fed swaps in 2008 and 2020 collectively hold lots of dollars. Their collective holdings of US safe assets amounted to an estimated $1.9tn at the end of 2021. (Their total foreign exchange reserves at the end of 2024 were about double that sum.) That $1.9tn is big money. It’s triple the previous maximum drawing on the Fed swap lines in 2008, and four times larger than the peak 2020 usage.

© Deutsche Bank

Leadership could arise among the Fed’s standing swap partners, the European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, Swiss National Bank, Bank of England, and Bank of Canada. The ECB and BoJ were the largest users of the Fed swap lines in 2008 and 2020, respectively. During the 2023 run on Credit Suisse, the SNB acquired unique experience in tapping the New York Fed for $60bn against US Treasury collateral under the FIMA (foreign and international monetary authorities) repo facility.

The coalition could enlist the Bank for International Settlements for technical support as agent as European central banks did in 1973-95. Or the BIS could serve as intermediary, as it did when the New York Fed lent dollars through the BIS to offshore banks in the 1960s to prevent funding crunches.

However, there is a major wrinkle: the $1.9tn is invested, and a crisis calls for cash dollars. In a world where the Federal Reserve refuses to allow access to its swap lines, would the New York Fed continue to provide same-day FIMA repo funding against Treasuries held in custody?

If it did, the coalition could arrange to access hundreds of billions of dollars in same-day funds. If the Fed did not, then it would end up providing ad hoc funding.

Without the FIMA backstop, heavy central bank sales of US Treasuries would rock the US bond market. Such selling could prod the Fed into the market as buyer of last resort — as in March 2020, before the FIMA repo was introduced.

Without the FIMA backstop, the Fed similarly would have to cap market repo rates if central banks sought to repo Treasuries for cash in size. However, the recent benchmark rate shift from dollar Libor to repo-based Sofer means that the Fed’s own domestic monetary transmission requires well-behaved repo rates.

One way or another, the coalition would need to work with the Fed to manage any “dash for cash.” Even a large pool of dollar reserves would not stack up to “whatever it takes” Fed swaps. Limits excite. It may be, as Eurosystem sources grimly noted to Reuters, that “there is no good substitute to the Fed.”

Nonetheless, a dollar coalition of the willing could pool trillions of dollars to backstop global dollar funding with no more than self-interested Fed help. An inferior lender of last resort beats no lender of last resort.

Loading…