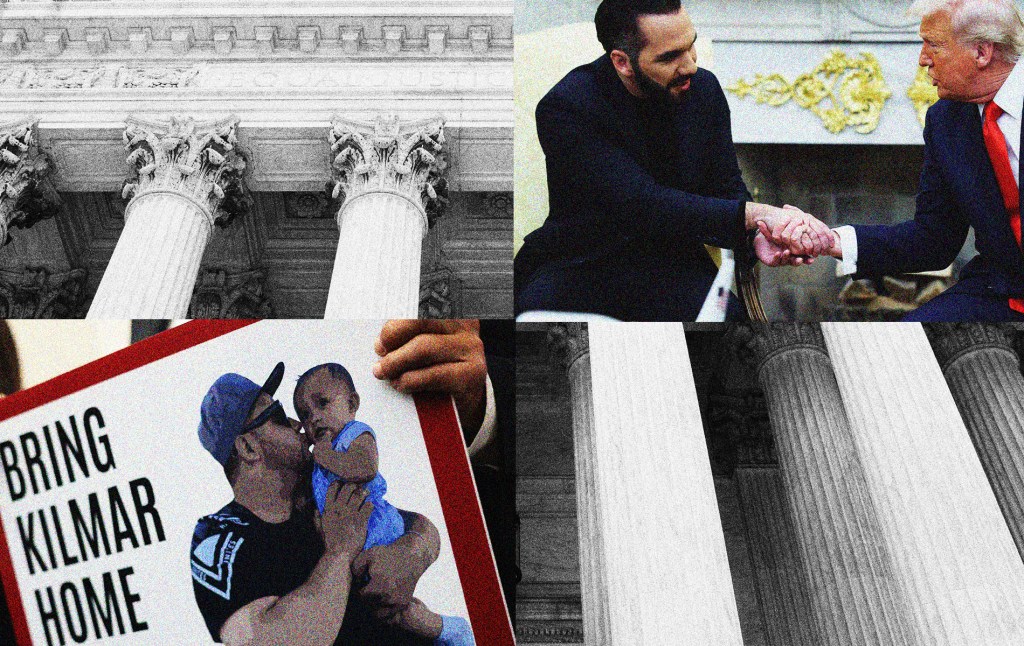

A Salvadoran immigrant who had been granted protection from deportation suddenly found himself at the center of a contentious national debate when U.S. immigration authorities deported him to El Salvador last month. The case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia has since evolved into a high-stakes confrontation between the judicial and executive branches over whether courts can compel the government to return individuals who have been wrongfully deported.

In the most recent development, on April 17, a three-judge panel of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the U.S. government’s appeal of a Supreme Court order mandating that the government facilitate Abrego Garcia’s return, stating that “the government is asserting a right to stash away residents of this country in foreign prisons without the semblance of due process that is the foundation of our constitutional order.”

This latest ruling marks a critical turning point in Abrego Garcia’s case, which has evolved from a bureaucratic error resulting in his deportation to a saga capturing international attention, illustrating the twists and turns that usually play out behind the scenes in the normal course of due process.

Who is Kilmar Abrego Garcia, and why was he deported?

Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia is a 37-year-old Salvadoran migrant who lived in Maryland with his family after entering the U.S. seeking refuge after he and his family were repeatedly extorted and threatened by gangs in El Salvador. After crossing into the U.S. illegally in 2012, Abrego Garcia was granted “withholding of removal” in 2019, meaning an immigration court barred his deportation to El Salvador due to what the court determined was a credible fear of persecution. This protection, a form of relief similar to asylum, meant that under U.S. law, he was not to be removed back to his home country.

Despite the existence of the court order protecting him, ICE detained Abrego Garcia on March 12 during a traffic stop and put him on a flight with other deportees to El Salvador on March 15. U.S. officials transferred him directly into a new Salvadoran “mega-prison” for alleged gang members. Although ICE acknowledged it made an “administrative error” in deporting Abrego Garcia, the Trump administration has justified this measure on the grounds that Abrego Garcia is affiliated with the MS-13 gang, though his supporters deny this claim. The 4th Circuit ruling directly addressed this contested accusation, stating that even if the gang allegations turn out to be true, the government cannot circumvent legal protections by deporting first and presenting evidence later.

What is ‘withholding of removal’ and how does it differ from asylum?

Withholding of removal is a form of relief under U.S. immigration law that prevents the government from returning a person to a country where they face a clear probability of persecution. While similar to asylum, it provides fewer benefits and does not lead to permanent residency or citizenship.

This protection is binding on the government and can only be revoked through specific legal procedures. A deportation in violation of a withholding order represents a serious breach of both immigration law and the international principle of non-refoulement, which aims to protect people from being returned to places where they face persecution.

Why has this deportation become legally significant?

Abrego Garcia’s deportation has sparked a pivotal legal battle in U.S. courts over the rule of law and executive compliance. Within days of his removal, his legal team sought relief, arguing the government had violated a binding 2019 court order. U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis took up the case and ordered the government to “take all measures available to facilitate [Abrego Garcia’s] return to the United States as soon as possible,” emphasizing that he never should have been deported.

The fight quickly reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which stepped in and directed the administration to “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s release from custody in El Salvador, effectively backing the lower court’s demand. This was a highly unusual intervention, as it essentially amounts to the nation’s highest court instructing the executive branch to reverse a deportation.

What is the current legal dispute about?

The core issue has become whether and how the government must comply with judicial orders to return Abrego Garcia. Justice Department lawyers have conceded that his removal was improper, but contend that ordering his return exceeds judicial authority, citing language in the Supreme Court’s ruling that deference is owed to the administration in conducting foreign affairs.

Facing mounting pressure, the administration later responded they would “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s return only if he could make his way to a U.S. port of entry—essentially saying they would let him back in if he showed up at the border. Xinis rejected this response as “contrary to the law and logic,” since Abrego Garcia remains imprisoned in El Salvador and is unable to present himself at a U.S. border crossing.

How have new allegations affected the case?

As the legal battle intensified, newly surfaced allegations of domestic violence complicated the narrative. On April 16, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released court documents revealing that Abrego Garcia’s wife had sought a temporary protective order against him in 2021 over claims of abuse.

According to Maryland court records, Jennifer Vasquez Sura filed for a protective order in May 2021, alleging serious incidents of domestic violence. In her sworn petition, she described being punched and scratched, causing bleeding, and another incident where Abrego Garcia became enraged, ripped her clothes, and chased her. These allegations were never adjudicated in criminal court; they appeared in a civil protective order application that was dismissed in June 2021 when Vasquez Sura failed to appear for the follow-up hearing.

Vasquez Sura has released a statement through her attorney, which explains that as a survivor of domestic violence in a prior relationship, she “acted out of caution” after a heated argument with her husband, seeking the protective order “in case things escalated.” She went on to say the couple subsequently worked through the situation privately.

In addition to the domestic violence incident, on April 18 Fox News published details of a 2022 traffic stop of Abrego Garcia after he was found speeding and driving with an expired license. Although the report of the traffic stop states that the officer suspected Abrego Garcia may have been participating in human trafficking since there were eight other individuals in the car but no luggage, Abrego Garcia was nevertheless released with a warning.

The timing of these disclosures are notable—they come after courts have ordered Abrego Garcia’s return. The administration seized on these allegations to argue that Abrego Garcia is not as sympathetic a figure as portrayed. In a social media post, DHS pointedly remarked that Abrego Garcia “was not the upstanding ‘Maryland Man’ the media has portrayed him as.”

The late emergence of potentially damaging allegations after deportation exemplifies the 4th Circuit Court’s concern that the government cannot circumvent established legal procedures by removing someone first and presenting justifications later. As the court noted, regardless of the accusations against him, Abrego Garcia “is still entitled to due process”—which includes the proper consideration of all relevant evidence through established legal channels before deportation occurs.

What does this case reveal about the U.S. immigration system?

The Abrego Garcia case demonstrates several important dynamics within the U.S. immigration system.

First, it highlights a new challenge to judicial authority in immigration cases. The 4th Circuit forcefully rejected the administration’s unprecedented claim that it can ignore court orders preventing deportation, an argument that, if accepted, would undermine fundamental due process protections that have historically prevented catastrophic errors—such as the mistaken detention or deportation of U.S. citizens, military service members, and others with clear legal rights to remain in the country.

Second, it highlights how quickly and deeply politicized immigration cases can become. White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt defended the deportation, referring to Abrego Garcia as “an illegal immigrant, a criminal and a terrorist,” and stating that “nothing is going to change the fact that [Kilmar] Abrego Garcia will never return to the United States.” On the other side, Maryland Sen. Chris Van Hollen recently made a highly publicized trip to El Salvador to attempt to secure Abrego Garcia’s release.

Third, it underscores the international complexities of immigration enforcement. Despite the administration’s claim that ultimate custody of Abrego Garcia now rests with El Salvador, El Salvador President Nayib Bukele claimed he “could not release” Abrego Garcia unilaterally.

What happens next?

As of April 17, Abrego Garcia remains behind bars in El Salvador, even as recent legal developments have strengthened his case for return.

The 4th Circuit’s ruling represents a significant legal setback for the administration, narrowing its options. The government must now either comply with the court orders or appeal to the Supreme Court, which has already indicated its position by directing the administration to facilitate Abrego Garcia’s release from Salvadoran custody.

The resolution of this case could establish important precedents about judicial authority in immigration matters and the remedies available when the government violates court-ordered protections. While the fate of Abrego Garcia remains undetermined, the Supreme Court has stated in a separate court case that people facing deportations should be granted “an opportunity to challenge their removal.”