Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

Like orbiting space debris, every loan that has been collateralized by an illiquid asset is a high-speed projectile with the potential to disable any other part of the system it impacts.

Complex systems can undergo what’s known as phase shifts, where the state of the system changes abruptly. The classic example of this is liquid water turning to ice. Since the mechanisms at work–temperature, saline levels, etc.–is known and measurable, then this phase transition is predictable.

Complex systems with emergent properties are unpredictable, and so their phase transitions catch us off guard. The system looks stable, as the risk of sudden instability resolving in a phase shift is not visible.

Emergent properties arise from the interactions of various parts of the system rather than from the characteristics of the parts themselves. Interactions in complex systems that are tightly bound –i.e. highly interconnected–are dynamic and so the consequences of unexpected interactions are unpredictable.

In other words, we think we understand all the possible interactions, but we’re forgetting second-order effects: first-order effects: interactions have consequences. Second order effects: consequences have consequences.

This illusion of control leads us to tinker with systems such as the global financial system to suppress any interactions we see as threatening the stability of the entire system. But this tinkering to lower risk has a hidden consequence.

As Nassim Taleb noted in a 2011 article: “Complex systems that have artificially suppressed volatility become extremely fragile, while at the same time exhibiting no visible risks.”

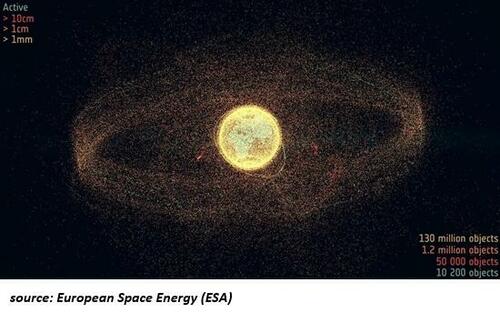

Which brings us to a second example of a phase shift: The Kessler Syndrome: The Kessler syndrome, proposed by NASA scientist Donald Kessler, describes a hypothetical scenario where the accumulation of space debris in Earth’s orbit triggers a chain reaction of collisions, creating even more debris, potentially rendering parts of space unusable.

While this is described as “hypothetical,” the potential for a Kessler Effect to occur rises sharply with the quantity of space junk / debris speeding around low-Earth orbits in what I call The Orbital Landfill, a space-age analog of The Landfill Economy we’ve created here on the planet’s surface.

And voila, the number of bits of high-speed debris is rising, along with the number of satellites being lifted into orbit: Catastrophe Looms Above: Space Junk Problem Grew ‘Significantly Worse’ In 2024 That’s brings us to the nightmare scenario that should fill you with dread: The Kessler Effect.

I submit that the Kessler Syndrome is an apt analogy for what may be happening in the global financial system: interactions that few anticipated are setting off second-order consequences that are themselves interacting with other parts of the system in unpredictable ways that will cascade, in effect clearing entire orbits of the global financial system.

So once a margin call impacts a functioning satellite and shatters it into random projectiles, the fallout / debris from that impact then strikes everything that is tightly bound to that part of the system.

These consequences then impact other parts, triggering margin calls and liquidation of assets that then shatter and those destructive projectiles become so numerous that they clear the entire orbit of functional parts of the system.

In a financial Kessler Effect, every critical element is shattered into dangerous debris that cascades through the entire global system.

Being tightly bound, the global financial system is exquisitely sensitive to cascading margin calls and forced liquidations of assets. Like orbiting space debris, every loan that has been collateralized by an illiquid asset (i.e. an asset that can’t be sold with the click of a button and the transaction clears second later) is a high-speed projectile with the potential to disable any other part of the system it impacts.

The problem with markets that Taleb described so succinctly is that the risk of apparently liquid markets freezing up and becoming illiquid is not visible until it’s too late to sell. Conventional market theory holds that there will always be a buyer to take an asset off a seller’s hands. But buyers disappear in crashes, as nobody wants to catch the falling knife.

Assets that were presumed to be liquid become illiquid, and their valuation plummets. This collapse of collateral then triggers margin calls (loans being called in, demands for cash) which then trigger more liquidations into an illiquid market.

And that’s how a Financial Kessler Effect clears entire orbits of the global financial system. What looked robust and low-risk is reduced to debris.

* * *

Loading…