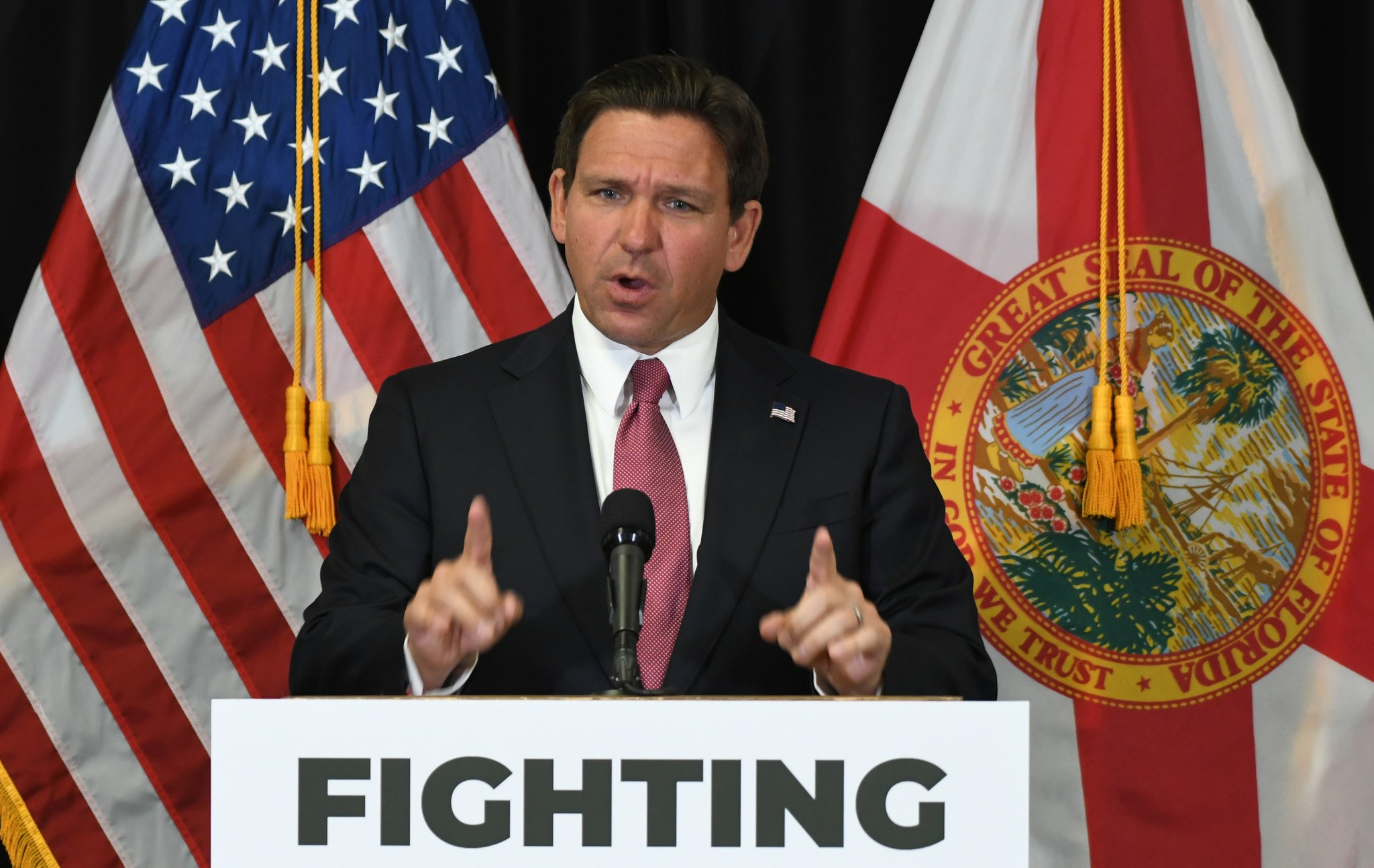

TALLAHASSEE—Gov. Ron DeSantis is eyeing a 2028 presidential run while his wife, Casey, readies a 2026 gubernatorial bid. But ahead of them lies a political minefield unlike anything the Sunshine State’s Republican power couple has experienced previously.

DeSantis wants another crack at the White House after coming up miserably short in the Republican primary last year versus President Donald Trump and would prefer to take his shot in 2028, the governor’s GOP allies and other party operatives and officials in the state capital told The Dispatch this month. The only unknown: whether DeSantis would opt to challenge Vice President J.D. Vance, who if he runs, could have the unequivocal backing of Trump and his Make America Great Again populist movement by then.

“He did it against Trump. Vance is not Trump. So I think the calculus for him jumping into that race against Vance would be a lot easier,” offered a GOP operative and staunch DeSantis ally, who, like most Republican insiders interviewed for this story, requested anonymity to speak candidly.

“I don’t see him, at this point at least, wanting to run an outsider campaign like he did in this last election,” countered a Republican operative also loyal to DeSantis. “But if Trump’s not going to weigh in, or his popularity’s down or J.D. makes a stumble, then I could see him being interested in it.”

DeSantis’ more immediate task may be helping his wife enter the August 2026 Republican gubernatorial primary, an announcement that could come as early as May after the current legislative session. The contest is being dominated early on by U.S. Rep. Byron Donalds, endorsed by Trump and counseled by his top advisers, although the first lady’s name identification is high, as are her personal approval ratings.

Florida’s first couple is working overtime to strengthen their relationship with Trump. DeSantis’ political team is soliciting prominent Florida Republicans to donate to the governor’s political action committees (Florida Freedom Fund, a state PAC, and the federal Restore Our Nation PAC) or requesting they keep their powder dry, confirmed a GOP lobbyist who was on the receiving end of one of those telephone calls. Additionally, the first lady is increasing public appearances alongside her husband.

Given an opportunity by The Dispatch to dismiss DeSantis’ 2028 ambitions, the governor’s political team declined. Likewise, the governor’s team did not deny that Casey DeSantis, 44, is actively preparing to launch a campaign to succeed her term-limited husband.

Notwithstanding the beating DeSantis took from Trump in the 2024 Republican presidential primary, the governor has generally enjoyed a charmed political life since setting his sights on Tallahassee in 2018: earning Trump’s endorsement in the GOP primary that year, winning a general-election nailbiter when Republicans suffered nationally, transforming himself into a nationally respected Republican figure in 2020 by resisting COVID-19 lockdowns and school closures, and solidifying Florida as a bona fide red state. From then on, the Legislature did whatever he asked, and easily won reelection in 2022 while raising north of $100 million for his White House bid.

DeSantis is still popular with Sunshine State voters, receiving a job approval rating of 53 percent and a net positive rating of 11 percentage points in a late March poll (slightly besting Trump’s 52 percent and 8 percent, respectively). But as the sun begins to set on his administration (his term will end in January 2027) and he and his wife chart their political future, obstacles abound. The Republican-controlled Legislature is bucking him at every turn, with state lawmakers questioning the governor’s emotional stability in interviews with The Dispatch (more on that later). DeSantis’ presidential aspirations may have to contend with Vance, and the first lady’s gubernatorial hopes already face a formidable hurdle in Donalds.

“The voters love the DeSantises. I think politicians are getting tired of [them]. They’re very difficult to deal with,” a senior Republican official said. “He is who he is, and I think that’s hurt him politically.”

Battling with Republicans.

Running for president and losing sometimes changes a politician. A campaign can expose personal shortcomings and challenge political positions. Some respond by making noticeable adjustments, either minor or major. But on a tolerably warm and only slightly humid sunlit April Fools’ Day in the Florida panhandle, Ron DeSantis seems, well, as Ron DeSantis as ever: driven yet defensive, girding for some battle or another.

During a brief news conference at the end of an event to promote the Hope Florida Foundation, a major initiative of the first lady’s that harnesses public and private resources to help struggling families, DeSantis snapped at a local reporter who asked why the organization hasn’t filed any tax returns. “We’re not going to let you try to smear a good program with this stuff,” DeSantis, flanked by his wife and sheriffs from across the state, said.

The governor, speaking inside the expansive Cabinet Room located on the subterranean level of Florida’s skyscraper Capitol building, wasn’t finished, turning his ire toward a relatively new opponent: the Republicans running Florida’s lower chamber.

“While you’re worried about filing paperwork, we’re worried about lifting Floridians up. We’re not worried about trying to play phony gotcha games,” DeSantis barked. “Go back to the House leadership office, talk to their staff, let them feed you some more B.S., try to recycle it. But nobody trusts you anymore, you don’t have any credibility because you’re always peddling the same B.S.” (DeSantis did say Hope Florida would file the missing tax returns.)

One of the raps on DeSantis throughout his political career—as a congressman from Jacksonville, as governor, and especially while campaigning for president—is that he’s a policy wonk more comfortable with data spreadsheets than people. He doesn’t like socializing with politicians or making small talk with voters. It was evident back in 2023 and early 2024, as DeSantis campaigned in early primary and caucus states, like Iowa, that doing so was not his strong suit.

That remains true today, and at least partly explains the problem he is having with a Republican-controlled Legislature, including the GOP supermajority in the House. Emerging from COVID and leading up to a Republican presidential primary in which DeSantis was initially the prohibitive frontrunner, Republican lawmakers accommodated the majority of the governor’s demands, a veteran party operative here said. “It’s not just a function of his term-limits,” this GOP insider said. “The real problem is that he has no political capital in that Capitol.”

That included a ban on abortion rights after the first six weeks of pregnancy that rubbed many of them—and Trump—the wrong way.

With Trump having knocked DeSantis down a peg, GOP lawmakers here say they feel they can finally tell the governor “no.” Take DeSantis’ current top priority, for example: eliminating the property tax. Republicans in the statehouse believe doing so would blow a massive hole in state revenue (Florida has no state income tax). They oppose DeSantis’ plan to make up the difference with a sales tax hike he argues would fall largely on foreign tourists.

“We are equal branches of government,” House Speaker Daniel Perez, a fiery Miami Republican, told The Dispatch during an interview in his office. “If there is a disagreement between the governor and myself, there is nothing wrong with vocalizing the disagreement.” The matter of whether his Republican colleagues in the House are feeding reporters dirt on Hope Florida is one such disagreement.

“There are no talking points we’ve given to reporters. There are no questions we’ve planted with reporters. Anything we want to tell the governor, we tell him to his face,” Perez said. “It does seem to me of late he has become more emotional—seems to be losing control of his emotions—and that’s unfortunate.”

“The guy is rattled,” added a Republican state senator, who requested anonymity to speak candidly. “He’s always been pretty aggressive. But I think what’s the difference now is for six years he had [legislative leaders] who took a knee. They took a knee on everything. … He’s never had to fight in this type of environment. And you say, ‘thank God he wasn’t elected president.’”

Meanwhile, Perez also took a subtle shot at DeSantis’ constant braggadocio for turning Florida red and creating a regulatory environment that has attracted millions of transplants from other states. The credit should be shared, Perez said, among former Republican governors Jeb Bush and (current senator) Rick Scott and the Legislature. “I don’t like it when Republican leaders try and take all the credit for the successes of today, because not one person that is a current leader of the Republican Party in the state of Florida can take full credit for all the wins.”

The animosity goes both ways. DeSantis has torched House Republicans at every turn for being insufficiently conservative. At an event at the governor’s mansion in March, the governor accused state House Republicans of “pettiness” and “stupidity,” saying they’re motivated by “grievance.”

“To have a GOP super majority—it isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on unless they act like a GOP super majority. What I see so far out of the Florida House of Representatives—they’re not trying to step on the left’s throat, they are giving a lifeline to the Democratic Party,” DeSantis said in a video clip the governor’s team shared with The Dispatch, as a visibly uncomfortable Evan Power, chairman of the Florida Republican Party, looked on.

“Are we in Florida? Or are we in San Francisco?” DeSantis asked, mockingly.

This intraparty feud was on full display this past winter during a special session of the Legislature DeSantis called to address immigration enforcement and better align Florida law with Trump’s immigration agenda. Both chambers of the Legislature initially balked at DeSantis’ proposal and instead approved a package that diluted the governor’s power to oversee the policing of illegal immigrants. But DeSantis, proving he still commands the bully pulpit, eventually muscled through legislation more to his liking.

“I ain’t budging an inch on what is right,” DeSantis said during that gathering at the governor’s mansion. It’s this relentlessness to drive an agenda, and the outcome it achieved on the immigration package, that supporters point to as proof that the governor still has the political juice to work his will in the Capitol—and extend his political future beyond it.

Still Trump’s GOP.

Despite the economic volatility unleashed by Trump’s erratic tariff strategy and the potential political implications for 2026 and beyond, today DeSantis and his wife rightly understand that Trump holds the keys to the future for any Republican who aspires beyond his current station. That includes Florida’s 46th governor and Casey DeSantis’ machinations to become No. 47. That might explain why DeSantis, responding to a question from The Dispatch during last week’s news conference at the Capitol, quickly dismissed concerns that Trump’s willingness to slap high tariffs on American trading partners threatens to gut foreign tourism, a major component of Florida’s economy.

“Casey and I had our kids at Legoland in Polk County a couple of weeks ago, and I’m getting stopped every 10 steps to take pictures—and 80 percent of the people were from Canada,” DeSantis said, disputing several credible reports of Canadians who regularly travel to Florida and other states boycotting the U.S. to punish Trump for tariffs targeting goods and commodities imported from north of the border despite the existence of the United States Mexico Canada Agreement he negotiated during his first term.

“The Canadians are coming; we’re going to continue to be a tourist hotspot,” the governor insisted.

The DeSantises are making progress in their effort to establish warm, long-lasting relations with Trump, agreed the nearly dozen Republican operatives The Dispatch spent time with in Tallahassee. But it’s not because Trump has made any special effort to repair a relationship that frayed as a result of their clash in the 2024 GOP presidential primary. Trump didn’t have to, after knocking DeSantis out of the race early and winning in November.

And DeSantis shouldn’t expect any help from White House Chief of Staff Susie Wiles.

In fact, if there’s a voice in Trump’s ear urging him to keep DeSantis at arm’s length, it might be Wiles, considered the top Republican operative in Florida before she helped guide him to victory in 2024 and assumed the role of his top aide. DeSantis and Wiles have remained at odds since 2019, when the governor effectively banished her from Tallahassee over claims of leaking to the press (which she has consistently, vehemently denied, though she did not respond to a request for comment).

So any rapprochement has been all DeSantis’ doing.

The governor has framed his legislative agenda as being in service to Trump’s agenda, such as the aforementioned immigration enforcement package. He talks with the president by phone regularly and is even helping Trump secure land for his presidential library (Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton is a leading candidate, although other sites are being considered). Plus, DeSantis and the first lady are making pilgrimages to Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s private residence and social club in Palm Beach, Florida, where the president has spent most weekends since inauguration.

Indeed, when asked to assess how Trump and DeSantis are getting along now, Republican insiders almost unanimously raised as evidence of mended fences the first couple’s early March golf outing with Trump that, as Fox News’ Paul Steinhauser reported, included breakfast together. DeSantis was back in South Florida this past weekend, golfing with the president’s son, Eric.

“They’re chatty,” a knowledgeable Republican source said, referring to regular Trump-DeSantis phone calls. “They call and catch up on policy stuff.”

Races to come.

Just how far DeSantis is willing to accommodate Trump in furtherance of his and his wife’s political aims could become clearer in the coming weeks.

Next month, the governor is expected to pick a permanent appointee to fill the vacant Florida chief financial officer post. In choosing replacements for other empty political positions, DeSantis has gone with loyal allies. That would suggest that for the CFO post, he is poised to select state Sen. Blaise Ingoglia, one of his biggest supporters in the Legislature.

But if DeSantis wanted to make a dramatic overture to Trump that reduces the potential for friction and greases his case for the president supporting him and his wife in future political endeavors, the governor would choose differently. State Sen. Joe Gruters, an occasional DeSantis antagonist and staunch Trump backer, is running for the post in 2026 regardless and already has the president’s endorsement.

“I actually think if he were to pick Joe, it would totally shake things up in his direction with Trump,” a Republican lobbyist in Tallahassee said. “It’s an opportunity for the DeSantis people. But I don’t know if they’re going to take it.”