I’ve never met Donald Trump nor had any dealings with him, and since I don’t watch television, I’d barely paid attention to his antics until his unexpectedly strong run for the White House began attracting heavy media coverage in 2015.

But some time ago I was privately meeting on other matters with one of Trump’s powerful and influential backers when Trump’s name happened to come up. Since I tend to be forthright and speak candidly about most things, I casually described him as an “ignorant buffoon.” I was hardly surprised that my interlocutor failed to reply to that provocative characterization, but I noticed the slightly embarrassed expression on his face and interpreted his silence as an admission that he quietly shared my own appraisal.

I strongly suspect that the worldwide tariff policies recently declared by Trump will soon cause more and more Americans, including erstwhile Trump supporters, to come to that same distressing conclusion.

Tariff policy is part of economics, and I hardly claim any great personal expertise in that discipline. Indeed, quite the contrary.

Back almost a dozen years ago, before my increasingly controversial writings rendered me far too radioactive for such things, I was invited to participate in a televised NYC debate on the economics of immigration policy, with one of my opponents being the prominent libertarian economist Bryan Caplan of George Mason University. The show was syndicated around the country and simulcast on NPR, and early on I boldly admitted my total ignorance of economics, declaring that not only had I never taken a class in that subject, but I had never even opened the pages of a single economics textbook.

However, I also suggested that much of economics constituted basic common sense and perhaps partly as a consequence of that approach, our side won the debate by the widest margin in the history of that series, with one of the opposing team members even shifting towards our position.

Given this history, my negative appraisal of Trump’s new tariff policies should obviously be taken with a large grain of salt but not necessarily completely disregarded.

During his successful 2024 presidential campaign, Trump had often promised to impose heavy tariffs upon those countries that he believed were unfairly benefitting from one-sided trade with America, and reindustrializing our country would be an important element of his plan to “Make America Great Again.” So his personal affinity for tariffs was hardly unexpected.

Indeed, soon after coming into office, he had used what he described as his economic emergency powers to impose heavy new tariffs upon much-demonized China, which was not unexpected. But he also declared that huge tariffs would be imposed upon goods from Canada and Mexico, our closest neighbors and friendly allies. This was a major surprise, not least because during his previous term he had personally negotiated his own USMCA North American free trade agreement with those same two countries.

Now for Trump as our 47th president to denounce and completely repudiate the policies of Trump as our 45th president was at least a little eye-opening.

However, over the next few weeks, his repeated suspensions, reversals, and modifications of these new North American tariffs led to many suspicions that they merely amounted to bluster, being international bargaining ploys aimed at bullying our neighbors and that they would only briefly remain in place. This considerably lessened their perceived impact upon the integrated regional economy that had grown into place since the 1993 enactment of the original NAFTA agreement under President George H.W. Bush.

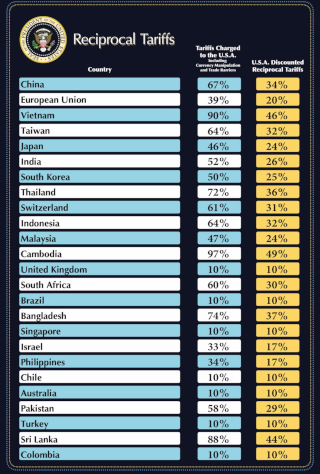

As a consequence, his announcement last Wednesday of sweeping new tariffs against almost every other country in the world hit like a thunderbolt. On April 2nd, Trump held up his chart showing those new tariff rates, and the figures were so astonishing that many observers probably felt that the plan should better have been issued a day earlier on April Fools’ Day.

For one thing, Trump’s actions were clearly illegal under American law. As many have noted, tariffs are obviously taxes, and according to the American Constitution, all tax bills must originate in the House of Representations and then be passed by both houses of Congress rather than be unilaterally imposed by our executive branch of government.

This has been the system for nearly our entire 250 year national history, including such cases as the notorious Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 and Trump 45’s own USMCA agreement signed in 2018.

But now Trump 47 declared that he would impose these new worldwide tariff rates by unilateral executive order, citing the emergency powers that he possessed under a 1977 law.

However, the “emergency” in question was apparently America’s ongoing deindustrialization of the last ninety-odd years. As prominent international economist Prof. Jeffrey Sachs pointed out, an “emergency” that had been taking place for nearly a full century hardly seemed the sort of “emergency” envisioned under that bill.

Yet that minor legalistic technicality barely scraped the surface of the very bizarre tariff rates that Trump had decided to impose against the 150-odd other countries of the world.

For example, our factually-challenged president declared that his new tariff rates were “retaliatory” and indeed the first column of the chart he displayed showed the foreign tariffs that had allegedly provoked his retaliation, but everyone quickly noticed that these figures were total nonsense. Switzerland hardly imposes a 61% tariff on American goods, nor does Vietnam maintain a 90% tariff rate against our products.

Instead these figures were merely calculated using a formula based upon America’s existing trade deficit in goods, which was something entirely different. So if another country sold us more goods than they themselves bought, that was described as due to a tariff even if no such tariff actually existed. In a perfect example of this absurdity, Trump incorrectly claimed that the penguins of Norfolk Island near Antarctica maintained huge barriers against American products, with his counter-vailing tariff of 29% aimed at punishing those water-fowl for their unfair trading practices.

Obviously, Trump’s claims justifying his new tariff rates were totally ridiculous, but they were actually ridiculous in several different ways.

For example, it’s undeniably true that for decades America has run a horrendous and growing global trade deficit with the rest of the world, most recently totaling $1.2 trillion during 2024.

However, suppose that this weren’t the case, and our trade in goods with the rest of the rest of the world were totally in balance, just as Trump wished it to be. Under those circumstances, we would naturally have trade surpluses with some countries and trade deficits with others, with all of the different figures netting out to zero.

But according to Trump’s framework, those countries with which we had a trade surplus would still be hit with a new 10% tariff while those with which we had a deficit would suffer much larger tariffs, and these would then be jacked up if those countries decided to retaliate. So the apparent goal and endpoint of Trump’s policies would be to sharply reduce or even eliminate all our trade with the rest of the world. Thus, Trump was self-sanctioning America much like he had sought to do against Iran, Russia, North Korea, and all the other countries he and previous administrations had regarded with considerable hostility.

Yet oddly enough Trump seemed to believe that cutting off the global trade of countries he didn’t like would severely hurt them, but cutting off our own trade would strengthen our country and benefit the American people.

His declared tariff methodology was even stranger. I noticed that all his international trade statistics focused only on goods while ignoring services.

So if our trade with some particular foreign nation were in perfect balance, with a deficit in goods exactly matched by a surplus in services, Trump would only consider the former not the latter, and impose large tariffs to reduce that problem.

Back in the 1990s, Paleoconservative trailblazer Pat Buchanan had advocated a sweeping set of controversial economic and political policies that greatly outraged our reigning intellectual establishment, with higher tariff rates among them. These positions led the Donald Trump of that era to harshly denounce Buchanan as “a Hitler lover.” But with the sole exception of Buchanan’s sharp criticism of Israel and its powerful American lobby, our mercurial current president seemed to have now fervently adopted nearly all of Buchanan’s ideas, but apparently attempted to implement them with an IQ that seems 30-40 points lower.

I’ve only casually explored Trump’s bizarre tariff proposal and given my self-proclaimed ignorance of economics, perhaps I even misunderstood some of its elements. But according to media reports, his proposal raises average American tariffs on goods more than ten-fold, from around about 2% to 24%. This will surely constitute a gigantic shock to our economic system.

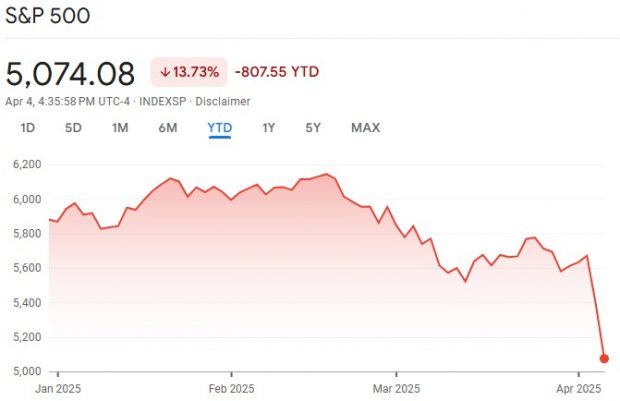

American businesses and the investors who own them seemed to see that shock in very negative terms, with our stock markets suffering their sharpest declines since the unprecedented collapse caused by the Covid epidemic of Trump’s previous term.

I’ve long suspected that our stocks were heavily over-valued, and Trump’s tariff announcement may have finally punctured that huge bubble, perhaps with financial consequences greater than he expected or intended.

For example, I’ve been rather surprised that high-profile tech companies that spent years annually losing billions of dollars have continued to maintain and even grow their market valuations, and perhaps these will now finally come down to earth, even with a gigantic thump. I had also thought that the release of China’s inexpensive and open source DeepSeek AI system would have a greater impact upon the American AI companies burning through so many billions of dollars each year, and maybe that will now happen.

Just a few days before the very sharp drop in American stocks, the Wall Street Journal had run a major article noting that over the last dozen years or so, the outsize returns in our stocks had drawn in unprecedented amounts of foreign investment. This inflow of funds might be reversed if stocks heavily fall, which would obviously magnify that effect.

Perhaps after their extremely sharp drops on Thursday and Friday, American stocks will stabilize themselves this week or even regain some of their lost ground. But perhaps the decline will still continue or accelerate.

The self-proclaimed goal of all of Trump’s wild tariff plans is the reindustrialization of American society, achieved by persuading major corporations to increase their domestic investment and relocate their factories back to our shores. But as numerous critics have pointed out, his policies seem rather unlikely to achieve that result.

Creating a major factory along with its associated sub-contractors and supply-chains is a very lengthy and expensive undertaking, likely to involve years and billions of dollars. So planning such major investment decisions requires a great deal of certainty that the factors responsible for the shift will remain in place for many years to come, thereby justifying such long-term capital expenditures. Uncertainty in the business climate will lead to the postponement of business investments.

Yet uncertainty is surely the watchword of Trump’s mercurial economic policies, with the recent announcements of crippling tariffs against Canada and Mexico having been repeatedly restricted, reversed, or delayed from day to day and week to week. Nobody had expected the sweeping worldwide tariffs announced last week, and given the ongoing collapse in global stock markets, nobody can say whether those tariffs—or even the president who issued them—will still be around in a few months’ time. Only a particularly foolish corporation would initiate long-term investment plans until the situation becomes much more clear.

So although Trump intended to promote a huge wave of new industrial business investment in America, the actual results seem much more likely to be the exact opposite.