Chag Pesach Sameach to those observing Passover this week. In this week’s Dispatch Faith and on our website today we’re featuring three writers with three different essays on Passover’s larger themes.

First up as the featured essay in today’s newsletter is Theodore Goldstein’s meditation on freedom and Passover. As he puts it, Passover doesn’t just commemorate freedom from something (in this case, slavery), but freedom for something. And that, he argues, is a universal theme.

Next up with a piece on our website that we’re giving you a taste of in the newsletter is someone whose work you’re probably used to listening to: Adaam James Levin-Areddy, who leads The Dispatch’s podcast and multimedia efforts. He argues in his essay that Passover was really a prelude to a more fundamental turning point in God’s relationship with his people: his giving them the Law.

And finally, we have an essay from Dispatch Contributing Writer Mustafa Akyol (whose work you’ve seen here before). He explains why Passover is the most-referenced story in the Quran and why its theme is so important to Muslims too.

Theodore Goldstein: Passover and the Master We Choose

When I was a child, my family had a tradition: Every Passover, we would go around the table and share something we felt enslaved to.

Our jobs, our schools, our responsibilities—everyone serves a master, and this tradition was an important part of our holiday celebration, as we reflected on the ancient story of our ancestral liberation and what liberation might look and feel like in our modern lives.

Passover, the festival of freedom, is one of if not the central holiday in the Jewish experience. The exodus from Egypt is so central to our religious existence that we recount it twice a day in our prayers. We spend eight days of the year (or seven, depending on where you are in the world and how you celebrate) refraining from eating leavened bread to remember the slavery from which we were freed.

But what is freedom? What does it mean to be a free person? This is the central question of Passover.

In the Passover Hagadah, we recite a teaching from first-century teach Rabban Gamliel: “in every generation a person must regard himself as though he personally had gone out of Egypt, as it is said: ‘And you shall tell your son in that day, saying: “It is because of what the Lord did for me when I came forth out of Egypt”’” (Mishnah Pesachim 10:5).

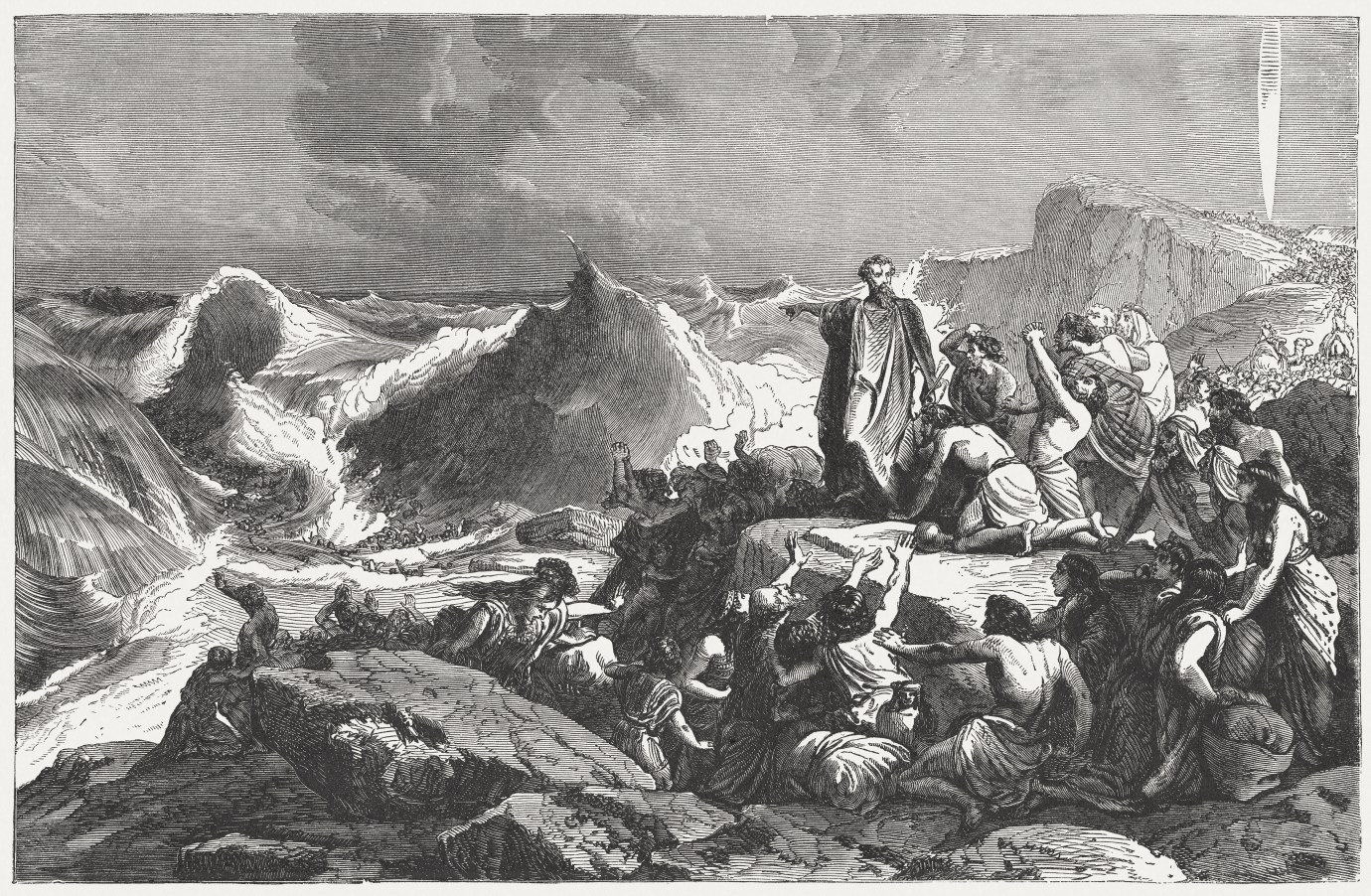

Thus every Jewish individual is obligated to see himself as though he personally stood at the Sea of Reeds and crossed it.

When we think about Passover, we usually think of the epic scenes, the great plagues and the splitting of the sea. But we often miss the subtle drama of the individual Jews marching into the sea, one foot after the other, leaving behind the lives they knew and heading into the great wilderness of the unknown.

In this way, Passover is the story of individual liberation as much as it is the story of collective liberation.

It is the story of thousands of individuals choosing to leave their old masters behind in search of something new, something better. The Jews are often called the “chosen people” because G-d chose to give us the Torah on Mount Sinai following the exodus from Egypt. But when they were fleeing, the Jews in Egypt did not know they would be chosen—they had not yet received the Torah.

“Chosenness” is a two-way street. G-d chose the Jews to receive the Torah, but only after the Jews chose to follow G-d into the sea.

One of the saddest parts of the Passover story, and one that gets left out in most retellings, is the story of the Jews who stayed in Egypt. The Jews who—even after witnessing 10 plagues ravage Egypt—were too afraid, too unwilling, too comfortable to leave their chains behind.

According to some interpretations, as many as 80 percent of the Jewish slaves did not wish to leave Egypt and stayed behind or died in the plague of darkness.

Freedom requires hard choices, and fleeing their Egyptian masters was indeed a hard choice for some of those slaves. Do I step into the Sea of Reeds and leave what I know behind, or do I stay upon the Egyptian shores and remain a servant to the master I was born to?

Passover is the annual reminder that we must constantly choose our own liberation, that we must constantly choose to cross the sea, lest we fall victim to the greatest enslaver of them all—comfort. Like the little bits of Chametz—leavened bread—that fill up a house between Passovers, our lives can easily become filled with little comforts, little compromises, little concessions that we have made against our own liberation.

One is only free insofar as they are able to choose what they do with their time. The little comforts in our lives are, by and large, not there by conscious choice. They slip into our lives, little by little, and we become accustomed to them and enjoy them.

If one is not careful, over time, these little unchosen comforts become so ingrained in our lives that we cease to recognize them and we live our lives, day to day, from comfort to comfort, without consciously considering whether or not that is the life we wanted to live.

Only by seeking out and destroying these little comforts, ruthlessly, as we seek and destroy the Chametz in our homes, can we rid ourselves of our slave mindset and prepare ourselves for our own individual liberation.

And while the rituals of Passover are meant for the Jewish people, the meaning of them and the search for individual liberation is ubiquitous.

To be a free individual is not easy. It requires constant hard choices.

But leaving behind our old masters is not enough. To be truly free, one must choose their own master. Before the exodus, G-d says to Pharaoh, “Let my people go, so that they may serve me.” (Exodus 8:16).

But most people only know the first half of that verse. It was only a few years ago, when I was teaching American history in an Orthodox high school, that I learned the second half of this verse—from one of my students as we were learned about the American Civil War and the emancipation of the slaves.

“But what were they freed to?” the student asked me.

“What do you mean?” I said. “They were freed from slavery, just like the Jews were freed from slavery in Egypt.”

“Yes,” he said, “but the Jews were freed to serve G-d. What were the American slaves freed to?”

His question, once I understood it, stopped me in my tracks. Freedom from slavery, from servitude to others, is only half of the story. The rest of the lesson of Passover is that G-d saved his people for something: service to him. So what do you do with that freedom once you have it?

This idea of positive freedom, the idea of freedom for something, is not just a Jewish idea talked about once a year—it is universal. The Declaration of Independence speaks of the universal rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

But one cannot pursue happiness subconciously. It requires personal introspection and hard work: introspection to identify the sources of one’s happiness, and hard work to center one’s life around that happiness.

In 2025, Americans have far more freedom than we know what to do with: freedom from bondage, freedom from oppression, freedom from want. But freedom from is insufficient.

True freedom is the ability to choose your master, the ability to stand at the foot of the mountain and say, “This is my G-d, this is the master I serve.” If you do not choose your master, you will end up serving someone else’s.

I am 26 years old. For my whole life, I, along with the rest of my generation, have been told and encouraged to seek freedom from all of the old oppressors of the past. Freedom from gender roles, social morés, and tradition more generally. This worldview has permeated the modern zeitgeist to the point where anything traditional seems to be bad, and anything that is not traditional seems to be good.

In a piece for The Atlantic, “Polyamory the Ruling Class’ Latest Fad,” Tyler Austin Harper writes:

… the present interest in polyamory more broadly—is the result of a long-gestating obsession with authenticity and individual self-fulfillment. That obsession is evident today in Instagram affirmations, Goop, and the (often toxic) sex positivity of an app-dominated dating scene, but its roots go back decades. As the historian Christopher Lasch wrote in 1977, this worldview “assumes that psychic health and personal liberation are synonymous with an absence of inner restraints, inhibitions, and ‘hangups.’” And what could offer more liberation than throwing off the constraints of one of humanity’s oldest institutions, monogamous marriage?

But has this freedom from tradition made anyone happier? Have people really freed themselves from the master of tradition, or have they just chosen another master by mistake? When I look at my generation, I do not see a generation of free people—I see a generation enslaved to the masters of others: They are enslaved to the social pressure of their peers, the politics of their professors, and whatever ideology is trending on social media on any given day. I saw this personally at my time at Princeton University, and from afar at college campuses all across America—students marching around campuses, disrupting classes, and occupying buildings, chanting slogans they do not understand about places they have never been.

But Passover is the celebration of individuals choosing their own liberation and forsaking their bondage to others.

Not everyone will cross the sea. No one can be forced to liberate themselves. Many people, most people probably, will continue to live their lives from comfort to comfort, from master to master, never truly thinking about and choosing which master they would like to serve.

So, this Passover season, whether you are Jewish or not, think about the masters you serve—did you choose them? The story of individual liberation and the difficulty of choosing one’s own master are as relevant today as they were 3,600 years ago when the Israelites stood at the banks of the Red Sea.

This Passover, let us all reflect upon our freedom, our individual freedom, and let us free ourselves from the masters of others. Let us live by our own choices, and not the choices of someone else.

This year, instead of asking my Passover table, “What would you like to be freed from?” I have decided to ask, “What would you like to be freed to?”

Adaam James Levin-Areddy: A Prelude to the Rule of Law

As Passover is about freedom, so too is it about the Law, Adaam James Levin-Areddy argues on the site. And that matters because it marked a fundamental shift in how God related to and interacted with his people, he says:

No doubt, God’s great and terrible wonders that delivered the Hebrews from slavery and toward their Promised Land deserve their annual recounting. But for Jews, liberation itself isn’t the culmination of the story, but the prelude. The exodus reaches its true climax 50 days later on Mount Sinai, where God reveals Himself to his freed nation in order to lay down the terms of a new social contract.

More than the miracles, or the crossing of the Red Sea, or the revelation of God in the desert (His presence was already ubiquitous!), it was receiving God’s Law—the Torah—that turned 12 tribes into a free nation.

The Law is the bedrock of the Jewish people and their relationship to the divine. A national constitution drafted by God and ratified by the people, obligating both. For the Israelites lost in the desert, the Law was a guide for surviving the burden of independence. It demanded of them to restrain their stubborn, defiant nature, while creating a system of ordered liberty. But for God, the Law meant something far more radical: a self-imposed limit on his own infinite sovereignty.

Mustafa Akyol: Why Passover Matters to Muslims Too

You may be surprised at the most referenced person in the Quran, says Mustafa Akyol in an essay on our site. It’s not Muhammad, or Noah, or Jesus. It’s Moses. And in second place? Pharaoh. That’s because of the outsized importance of the exodus account for Muslims.

One can wonder, at this point, why this biblical story of the Israelites was so important for the Quran, which emerged almost 2,000 years later, in seventh-century Arabia, addressing a totally different people: the Arabs. The answer that I offer in my book The Islamic Moses, is that those first Muslims, the followers of Muhammad, identified themselves with the Israelites. They, also, were monotheists who were persecuted by a pagan people—the polytheists of Mecca—and they also yearned for liberation. Thus the biblical story of Moses became an archetype for their own journey. And the Israelite exodus from Egypt became a template for their own hijrah, or migration, from Mecca.

Which points to a greater truth: Islam, just like Christianity, is deeply intertwined with Judaism. As the late, great Jewish historian Shelomo Dov Goitein once put it, Islam is even “from the very flesh and bone of Judaism. It is, to say, a recast, an enlargement.” This is also why, just as there is a “Judeo-Christian” tradition familiar to most Americans, there is also a “Judeo-Islamic” tradition, as dubbed by another esteemed Jewish historian, Bernard Lewis.

More Sunday Reads

- The dictatorial regime of Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua is ramping up oppression of the Catholic Church there, going so far as forcing priests to submit their homilies to police officers prior to delivering them. Edgar Beltrán reports for The Pillar: “According to a Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW) report issued last week, Catholic priests in several dioceses are now required to go to the nearest police station for interrogation on a weekly basis. Some of these priests have said they are assigned a permanent surveillance official and are warned that they cannot leave their community without authorization. This last provision is especially affecting dioceses with large numbers of exiled priests, such as Matagalpa, which have relied on priests from other dioceses coming in on a weekly basis to serve parishes with exiled pastors. In the interrogation, these priests are reportedly forced to present copies of their homilies to the police to verify they do not contain any messages critical of the regime. Local outlet ‘La Prensa’ reported that in other dioceses, priests are not required to go to the police station, but instead the police go to the parishes and ask them for a summary of the parochial weekly activities. ‘They come to the parish and ask for the weekly schedule of activities of the priest and, if possible, the bishop. … They must include the Masses, mission activities, meetings with pastoral agents, and request permission if they leave their jurisdiction,’ a priest told La Prensa. … A source close to the Nicaraguan bishops’ conference told The Pillar that an increase in persecution last summer was believed to be a pressure campaign by the government, to force exiled bishops to resign their sees in order to be replaced by bishops who were friendly to the government. Similar moves could be attempted again, they warned.”

- Big news in the world of evangelical Christianity came this week when Trinity Evangelical Divinity School (TEDS), located near Chicago, announced it was closing its campus and merging with its sister school in British Columbia, Canada. For decades, TEDS stood apart from either pole on the spectrum of Protestant seminaries. Collin Hansen, the editor-in-chief of The Gospel Coalition and a TEDS alumnus, wrote about the legacy of the institution. “TEDS, as it rose to prominence under its second dean Kenneth Kantzer and employing other post-war evangelical leaders such as Walt Kaiser and Carl F. H. Henry, helped American evangelicals recover from the fundamentalist/modernist controversies of the early 20th century, as well as the inerrancy dispute that erupted at Fuller Theological Seminary in 1962. By the early 21st century, TEDS alumni including David Wells, Mark Noll, Doug Moo, and Craig Blomberg held research positions in other seminaries, while Michael Oh led the Lausanne Movement. TEDS also hosted the first meeting of The Gospel Coalition nearly 20 years ago, in May 2005, when Carson and Tim Keller convened several dozen North American pastors who shared their concern for restoring a confessional core to evangelicalism. TGC held its first national conference at TEDS in 2007, shortly before I left my job at Christianity Today and enrolled at TEDS. I first met Keller in the TEDS chapel, where he delivered his famous address on gospel-centered ministry. TEDS hosted several subsequent meetings of TGC’s Council, and Carson hired me at TGC upon my graduation from TEDS in 2010. With this history of evangelical leadership, the reason for the closing of the TEDS campus near Chicago is ironic. TEDS couldn’t survive the growth and spread of neo-evangelicalism across the United States in the last half-century. When Kantzer stepped down as TEDS dean in 1978, the evangelicalism we know today—populated and sometimes dominated by prosperous Southern Baptists—didn’t yet exist. That same year, a group of concerned Southern Baptists led by Paul Pressler and Paige Patterson met to discuss how they could shift the largest Protestant denomination in a conservative direction. That plan began to unfold in 1979 with the election of Adrian Rogers as the convention’s president. But it took until 1993 for that strategy to result in Mohler’s presidency at SBTS. And where did Mohler turn for a speaker at his inauguration? Henry, who reunited with Billy Graham, his longtime collaborator in such neo-evangelical ventures as Christianity Today.”

A Good Word

As communities in Southern California continue their recovery from devastating wildfires earlier this year, so does the Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center, which has existed for more than a century—until it was destroyed in the fires. But the community around it, including from other religions, has stepped up to help as Passover begins, as Deepa Bharath reports for the Associated Press. “Thirty of the synagogue’s 435 families lost their homes and even more were displaced. As the major Jewish festival approaches, it’s hard not to see the Passover story reflected in this post-fire reality, said Melissa Levy, the temple’s executive director. Passover, which begins at sundown Saturday, commemorates the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in ancient Egypt, including their 40-year journey through the desert. It is celebrated with a special meal called a Seder, the eating of matzo or unleavened bread, and the retelling of the Exodus story. ‘The synagogue itself and our people are doing a lot of wandering right now, and having to focus on togetherness and resiliency is a theme that hits home harder than usual this year,’ Levy said. The congregation has received overwhelming support from the community. First United Methodist Church opened its doors so they could continue to hold weekly Shabbat services, their Passover Seders will be held at Pasadena City College, and a synagogue member is sponsoring the second night’s dinner. ‘The outpouring of support we’ve received reminds us that we’re not alone and we’re not wandering alone,’ Levy said. ‘It’s a good reminder that we all are part of one human family and that the purpose of religion is to make ourselves the best we can be so we can repair the world and take care of each other.’”