By Dhaval Joshi of BCA Research

Mission Impossible: 2 Percent Inflation – The Sequel

Executive Summary

- Hitting and sustaining a precise 2 percent inflation target is more about luck than judgement. It requires both the starting point for inflation expectations and any inflation/deflation shock to combine perfectly to 2 percent.

- The euro area and Japan got lucky, because the pandemic inflation shock moved their inflation expectations close to the 2 percent target. But the US and UK got unlucky because the inflation shock moved their inflation expectations away from the 2 percent target.

- Hence, relative to current rates and expectations, the BoJ has the greatest scope to increase rates; the Fed and the BoE have limited room for manoeuvre; and the ECB has the greatest scope to cut rates.

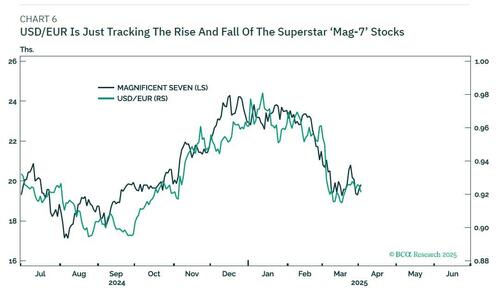

- FX markets will also be influenced by capital flows into and out of risk-assets. Specifically, USD/EUR is just tracking the rise and fall of the superstar ‘Mag-7’ stocks.

- Tactically, this means that a relief rally in Mag-7 will cause a relief rally in the dollar.

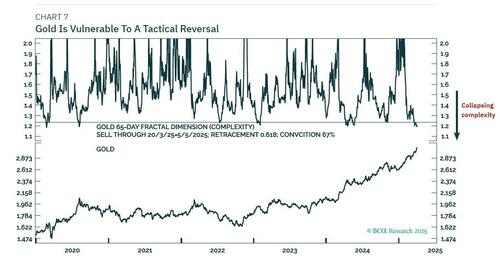

- A relief rally in the dollar also implies a tactical reversal in gold, confirmed by gold’s collapsed 65-day price complexity.

- On a longer-term horizon though, our favourite currency is the Japanese yen.

Tariffs have rekindled fears about inflation at a time that most economies’ inflation rates are already above central banks’ 2 percent targets. But after the pandemic inflation shock, the current low-single digit inflation rates feel like bliss. Causing some commentators to argue: can we really distinguish between low rates of inflation – and if not, then why not settle for inflation at 3 or 3.5 percent rather than the quasi-religious commandment of 2 percent?

To support this argument, some commentators have dug up an archive op-ed by the late Paul Volcker, What’s Wrong With the 2 Percent Inflation Target – Bloomberg

Volcker’s overarching point was that in trying to manage an economy, “false precision can lead to dangerous policies”. Price stability is that state in which expected changes in the general price level do not effectively alter business or household decisions. But, said Volcker, it is ill-advised to define that state with a point target, such as 2 percent.

Volcker was only partly right. He was right about ‘false precision’ when inflation is below 2 percent, but he was wrong about it when inflation is above 2 percent. Below 2 percent, inflation is imperceptible. So, yes, the distinction between 1 percent and 2 percent is a false precision. But above 2 percent, inflation becomes perceptible. Meaning that there is a big difference between imperceptible 2 percent and perceptible 3 percent.

Crucially, therefore:

There is a huge onus for central banks to bring inflation down from above 2 percent to at, or below, 2 percent.

There’s A Huge Difference Between 2 Percent And 3 Percent Inflation

The human brain cannot distinguish between very low rates of inflation, a range we just perceive as ‘price stability’. In ‘Real-Feel’ Inflation: Quantitative Estimation of Inflation Perceptions by Michael Ashton : SSRN Michael Ashton confirms that “it would be challenging for a consumer to distinguish 1 percent inflation from 2 percent inflation – that fine of a gradation in perception would be extremely unusual to find.” As the entire range of ultra-low inflation just feels like one state of price stability, sub-2 percent inflation does not alter business or household decisions.

Still, cumulative sub-2 percent inflation over years will eventually result in a meaningful increase in prices. Why do we not notice this? The answer is that our productivity also increases at a rate of 1-2 percent. And to the extent that our wages increase in line with our productivity, we will not notice any loss in spending power when inflation is running at, or below, 2 percent.

Above 2 percent though, there is a phase-shift. We do notice higher rates of inflation, both in the short-term and the long-term, so it alters business and household decisions. This makes it crucial for central banks to phase-shift inflation and inflation expectations from the perceptible 3 percent back to the imperceptible 2 percent or below. Yet this is easier said than done because of the way that inflation expectations are formed.

Inflation Expectations In The US And UK Will Stay Too High

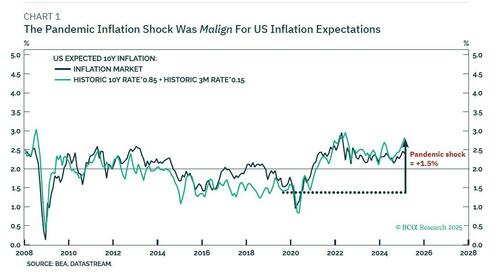

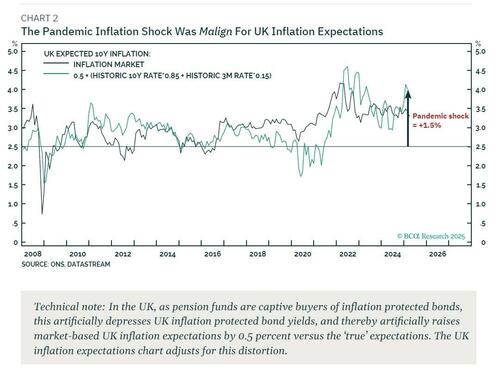

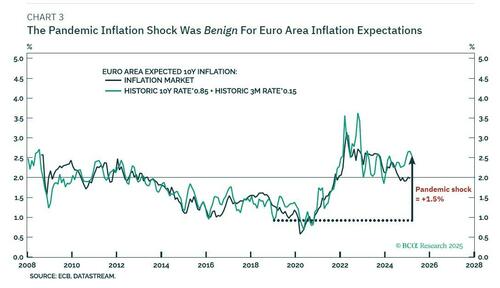

Long-term inflation expectations are nothing more than a simple weighted average of long-term historic inflation and extremely recent inflation (Charts 1-4). But the long-term historic component dominates with an 85 percent weighting. Specifically:

10-year expected inflation = 0.85 * 10-year inflation + 0.15 * 3-month inflation

This basic maths for inflation expectations has a crucial takeaway: inflation or deflation shocks that cause the long-term historic inflation rate to gap up or gap down will also cause long-term inflation expectations to gap up or gap down.

Or, put in simple English: Inflation and deflation shocks stay in the collective memory for a long time. This leads to another crucial takeaway. The pandemic inflation shock caused long-term inflation expectations to gap up by about 1.5 percent in every major economy. But depending on where those inflation expectations started, the inflation shock was either ‘benign’ or ‘malign’.

In the euro area and Japan, where long-term inflation expectations were well below 2 percent, the pandemic inflation shock was benign – because it finally lifted those inflation expectations to the required level of 2 percent.

But in the US and the UK, where long-term inflation expectations were close to 2 percent, the pandemic inflation shock as malign – because it lifted those structural inflation expectations to well above the 2 percent threshold at which inflation becomes perceptible.

In the case of the US and the UK therefore, the pandemic inflation shock must be neutralized by a new deflationary shock to restore long-term inflation expectations back to 2 percent. But the source and timing of that deflationary shock are unclear.

Until such a deflationary shock arrives:

Long-term inflation expectations in the euro area and Japan will be close to the sweet spot near 2 percent, while those in the US and the UK will be stuck uncomfortably above 2 percent.

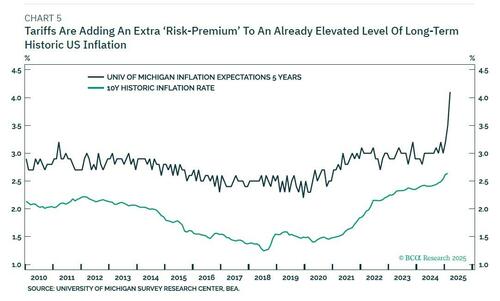

Tariffs will only make matters worse, as it will add an extra ‘risk-premium’ to an already elevated level of long-term historic US and UK inflation (Chart 5).

The Euro Area And Japan Got Lucky, The US And UK Got Unlucky

Ten years ago, I wrote a heterodox report: Mission Impossible: 2% Inflation. In it, I argued that hitting and sustaining a precise 2 percent inflation target is more about luck than judgement. Rather like pulling a brick with an elastic band to a precise target. To end up at the target, you need to get lucky. Hitting the inflation target requires both the starting point for inflation expectations and any inflation/deflation shock to combine perfectly to 2 percent.

Ten years on I stand by that report. The euro area and Japan got lucky. Their pre-pandemic structural inflation expectations at below 0.5 percent combined perfectly with the +1.5 percent pandemic shock to get close to the 2 percent sweet spot.

Conversely, the US and UK got unlucky. Their pre-pandemic structural inflation expectations near 2 percent combined with the pandemic shock of +1.5 percent to take those expectations well above the 2 percent sweet spot.

Versus the current level of interest rates and expected moves through the next year or so, we can therefore say:

The Bank of Japan has the greatest scope to increase rates; the Fed and the Bank of England have limited room for manoeuvre; and the ECB has the greatest scope to cut rates.

In the rates market this means short Japanese rates; neutral US and UK rates; and long euro rates.

The FX markets are more complicated because they will also be influenced by capital flows into and out of risk-assets. Specifically, USD/EUR is just tracking the rise and fall of the superstar ‘Mag-7’ stocks (Chart 6).

Tactically, this means that a relief rally in Mag-7 will cause a relief rally in the dollar.

A relief rally in the dollar also implies a tactical reversal in gold, which is confirmed by gold’s 65-day price complexity reaching the point of collapse that has signalled previous tactical reversals (Chart 7).

More in the full BCA note available to pro subs.

Loading…