Back to the future, of foundations.

The below article by Jeffrey Hart originally appeared as a chapter, “Foundations and Social Activism: A Critical View,” in 1973’s The Future of Foundations, edited by Fritz Heimann. The volume was compiled as background reading for participants in an American Assembly meeting about philanthropic foundations at Columbia University’s Arden House in New York in 1972.

Affiliated with the university since 1950, the American Assembly fostered research-based public conversations about major issues facing the country. It was founded by Columbia’s then-president Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 2023, it merged with the university’s Incite Institute, which has kindly granted The Giving Review permission to republish the chapter’s contents.

The ’72 Assembly program on foundations was supported by, among others, the Rockefeller, Henry Luce, and William Benton Foundations.

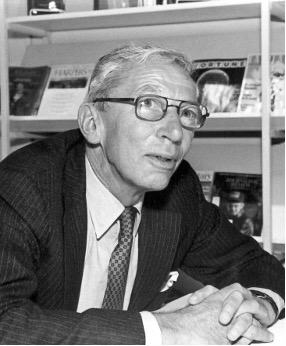

Hart was a professor of English literature at Dartmouth University, a senior editor of and writer for National Review, and a syndicated columnist. In 1968, he worked on the presidential campaign of Ronald Reagan, and he served for a time as a speechwriter for President Richard Nixon. The Dartmouth Review was founded in his living room in 1980. He died in 2019.

As with Hart’s 1969 call for philanthropic reform in National Review about which we wrote last November, his The Future of Foundations chapter is a reminder of a previous willingness on the part of conservatives to offer harsh criticism of Big Philanthropy—along with that which gave, and still gives, rise to such criticism.

***

Popular Wariness

In both practical and theoretical terms, the tax-free foundations face serious difficulties, and, for those who have eyes to see, neither category of difficulty seems at all likely to fade silently away. May I say that this situation is by no means a source of joy to me, since I do think the foundations have a valuable role to play in our society—though, as will be seen, my conception of that role differs from the one widely if not generally held in the foundation world. But, on the other hand, I cannot grieve overmuch for the foundations in their predicament, for they themselves have done much to create it, and they continue to exacerbate it. As in Greek tragedy, here too character may be destiny. In any case, as I see it, the prospect before the foundations today is one of deepening public malaise and festering rebellion, with, off at the end, only bleak prospects.

During the campaign leading up to the 1972 elections, we heard a great deal about a resurgence of “populism,” and politicians as diverse as James Buckley, Harold Hughes, Fred Harris, George McGovern and George Wallace, sensing the national mood, made one form or another of populist appeal. The common denominator in all of this was the feeling on the part of the ordinary American that he was being put upon by one or another feature of the system—that vested interests, government agencies, the Supreme Court, the rich, or the tax structure were impinging upon his life in a malign way and that he, himself, could do little about it. George McGovern, on the left, campaigned against “tax loopholes,” among other things; on the right, George Wallace has attacked busing orders, pointy-heads in the bureaucracy, and tax-free foundations. But beneath these differences in formulation the appeal was essentially the same; it is a recurrent one historically and as old as the republic; it is essentially the appeal to the principle of equality against privilege, recognizable in Jacksonian democracy or in the movement that followed William Jennings Bryan, and it becomes a powerful political current when it speaks to the condition of important segments of the population, as it apparently did in 1972.

But this populism is not merely an election-year phenomenon, especially as it bears upon the tax-free foundation. Beginning in February 1969, the House Ways and Means Committee, under the chairmanship of the formidable Wilbur Mills, began a long-awaited and widely feared inquiry into the behavior of the foundations, and Mills’ recommendations at length passed through the legislative process and were included in the Tax Reform Act of 1969, about two-thirds of which is devoted to the regulation of foundations. This law, incidentally, represents the most extensive regulation yet attempted by Congress of the more than twenty-six thousand widely varying American foundations.

The Act does not appear to have been found to be particularly onerous by the foundations. Accountability and auditing procedures were tightened up in response to the legislation; the 4 percent tax on foundations’ investment income produced a modest return to the federal government. So on the surface all seems tranquil. In the Act, however, a kind of floating mine is present in the form of the provision which prohibits foundations from using their tax-free funds to “influence any legislation through an attempt to affect the opinion of the general public or any segment thereof.” So far this and other provisions of the Act bearing upon the political behavior of foundations have been broadly interpreted and have not—it is generally agreed—much inhibited the activities of the foundations. That floating mine in the Act is therefore, as it were, unarmed; but it is also clear that any unduly risqué political initiative would result in the prompt arming of that floating mine.

Foundation Vulnerabilities

The hearings in 1969 before Chairman Mills’ committee were not, of course, the only prominent manifestation of public concern about the activities of the foundations. At about the same time, a private commission headed by Peter Peterson, Charles Percy’s successor as chairman of the board at Bell and Howell, was raising its own questions about foundations. Ramparts magazine on the left, as well as National Review and the American Conservative Union on the right, were calling attention to what they perceived, from their different standpoints, as the abuses of foundations. And of course the legendary Wright Patman, congressman from the First District of Texas—and genuine populist long before the current vogue of populism—had been conducting throughout the decade of the 1960s an exhaustive investigation of the foundations and accumulating thousands of pages of testimony.

By 1969, the year of the Tax Reform Act, the tax-free foundations had entered into the political consciousness as an issue, as, indeed, a problem. The provisions of the Tax Reform Act, moreover, ought to be regarded by the foundations with a loud sigh of relief, the best they could hope for under the circumstances. For by 1969 the position of the foundations was highly vulnerable. In 1972, in addition to the populist noises made by George Wallace and others, Representative Patman announcing that his Banking and Currency Committee was getting ready to reopen the entire question of the foundations.

As the decade of the 1960s came to an end, the foundations found themselves suddenly vulnerable for three main reasons. The first two are straightforward enough: (1) many were operating wholly or in large part as tax dodges, and (2) many were frivolous to the point of cookery in the way they disposed of their tax-exempt funds. Though these two kinds of abuses are serious, they are not especially complicated, and the Tax Reform act of 1969 moved, at least tentatively, to correct them. The third reason for the foundations’ vulnerability, however, is a deeper and more complicated thing. The huge foundations, such as Ford and Rockefeller, dispose of enormous amounts of money and exercise considerable power; yet they are run by men elected by no one, and accountable only to self-perpetuating boards of directors. During the 1960s, moreover, these large foundations to an increasing degree involved themselves in the political arena. Their power was brought to bear for various interests in the nation and against others. Yet this power was perceived, correctly, as arbitrary power, unaccountable and therefore, in the strictest sense of the word, irresponsible.

Before returning to this third, and difficult question about the foundations, a word or two about the first two problems may be in order. First of all, foundations have been proliferating at a fantastic rate. Two thousand new ones came into existence in 1968 alone. And the criteria for starting a foundation seemed almost infinitely elastic. Wright Patman turned up foundations supporting mistresses, widows, divorcées, foundations to recruit football players, and foundations to underwrite banquets. One man set up a foundation, donated his house to the foundation, then continued to live in the house, charging his expenses off to the foundation. The possibilities seemed endless. Your foundation could have your portrait painted or your biography written, thus making contributions to “art” and “history.” Foundation such as Ford ($3 billion), Lilly ($900 million), Rockefeller ($830 million), Duke ($425 million), and Carnegie ($320 million) are the stratospheric peaks of the Foundation Range. Down in the foothills, however, there are some small but in their way gorgeous protuberances. Most foundations are in fact quite small, relatively speaking. Two-thirds have assets of less than $200,000, and make grants totaling less than $10,000 annually. Some of the smaller foundations are marvels to behold. Stewart Mott, Jr., for example, set up his own foundation called Spectemur Agendo, Inc., which gives away some $80,000 per year. Mott proudly describes the recipients of his largesse as “a variety of organizations in the fields of extra-sensory perception, human sexual response, aberration and hippie-oriented urban service.” In 1972, Mott’s fancy turned much more political.

But the gut issue concerning foundations is neither their use as tax dodges nor their use by kooks and eccentrics. The deep issue concerns the role of the larger foundations as a kind of shadow government, disposing of substantial political and social power, and using that power in ways that are in fact highly questionable. Though the foundations to an increasing degree are acting as a political force, and though they make no bones about their desire to act as a political force, they are not responsible to any electorate and so cannot be voted out of office if their political policies are perceived as undesirable. Because of their tax-exempt status, moreover, they are undertaking these activities with public money—money, that is, which otherwise would have found its way into the federal treasury and been used for public purposes.

Now in reply to these points it could well be urged that foundations are not the only politically potent entities enjoying tax exemption. It could be pointed out that the income of labor unions is tax-exempt and that labor union dues are tax deductible. Businesses have a good deal of latitude as regards the activities they can deduct as business expenses. And these entities are often active politically in ways both direct and indirect. Why, then, single out foundations for special opprobrium?

Two answers may be given. First, the political activities of labor unions, for example, are the subject of extensive regulation. Tony Boyle, president of the United Mine Workers, faced a five-year jail term for violating such regulations. And, in general, the political use of tax-exempt money is the subject of continuing federal scrutiny.

But beyond that, however, is the fact that there is a difference in kind between, on the one hand, labor unions, veterans’ organizations and businesses, and, on the other hand, the foundations. Each of the former represents a specific, concrete interest in the community. It is generally recognized that the member of labor unions have common interests; it is also recognized that some of those interests are political; and it is generally agreed that it is right—the agreement is embodied in legislation—that those political interests be pursued. The same is true of veterans’ organizations and businesses. They are concrete, identifiable interests. But this is not true of the foundations. What interest do the foundations represent? What, indeed, is a foundation but a large amount of money presided over by a small number of executives, individuals largely unknown outside their own circle, whose opinions and goals are themselves largely unknown. It is by no means obvious that the foundations, politically considered, represent an interest in the community which ought to be fostered. The analogy between the tax-exempt foundation and the tax privileged entity like the labor union therefore breaks down immediately.

Political Action and Social Change

Until recently, the eleemosynary activities of the foundations, insofar as the general public apprehended them at all, were relatively noncontroversial. The foundations supported medical and scientific research, they provided some support for scholarship and the arts, they were much involved with education and conservation. By rough common consent, all this was “legitimate” activity for tax-exempt capital. In addition, such benign activity was self-evidently consistent with the intentions—on the surface, at least, altruistic—of the men who had started the foundations.

During the 1960s, however, all this underwent a sharp change, and once again, as in the days of the robber barons, Ford and Rockefeller were in a fair way of becoming hated names in the land, for the great foundations began to involve themselves aggressively in political activities, bringing their vast resources to bear in ways that pit one group against another. “In the U.S.,” as Fortune noted approvingly, “the foundations have developed into a powerful force for social change and human betterment—a third force, as it were, independent of business and government.”

A ”third force” indeed! The country has made up its mind, as above, about the legitimate activities of labor unions, veterans’ groups, and businesses—but it is only beginning to consider the role of the tax-exempt foundation.

And while I am quoting Fortune, I would like to ponder, indeed to savor, some of its rhetoric, because I have found that rhetoric echoing in many a place: “the foundations have developed into a powerful force for social change and human betterment.” It seems here as if “social change” and “human betterment” are almost the same thing, or even exactly the same thing. And I would like to remember that adjective “powerful.”

But the expression “social change,” which has such a positive connotation in Fortune’s rhetoric, and in the rhetoric of foundation meetings, conferences, symposia and apologia, is, after all, a complicated and ambiguous thing.

The fall of Troy, after all, was a “social change.” The Greeks no doubt considered it a change for the better. The Trojans might have entertained their doubts. If the Grecian assault upon Troy had been carried out with funds to which the Trojans themselves had contributed—if, for example, the wooden horse had been built with tax-exempt funds accumulated in Troy itself—then, on a reasonable view, the Trojans would have had grounds for complaint.

The Entrance of the Wooden Horse into Troy, by Gillis van Valckenborch, 1598. License: Wikimedia Commons.

In the American context, one man’s desirable social change may another man’s ruined neighborhood, or disrupted way of life, or lost election. There is in fact no reason why the phrase “social change” should have a hopeful ring at all. Change is, after all, merely change. And when you get down to specificities, here is what the major foundations mean by that hopeful phrase, “social change”:

- In 1967, the Ford Foundation, working through the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), put $175,000 behind a voter registration drive in the Negro areas of Cleveland, Ohio. McGeorge Bundy has defended this, with spectacular disingenuousness, as merely an effort to expand “democratic participation.” But, as he knows, there was no way in which such a drive could fail to help Democratic nominee Carl Stokes, a Negro, who, in fact, was elected. Insofar as Seth Taft, Stokes’ opponent, paid higher taxes because of Ford’s tax-exempt status, Taft was actually contributing to his opponent’s election. Insofar as the larger number of voters who voted against Stokes were paying higher taxes for the same reason, they too were subsidizing with their own money the campaign of the man to whom they were in fact opposed.

The hypocrisy here on the part of the Ford Foundation goes very deep. Bundy invokes “democratic participation” as the neutral rationale for his voter registration drive. Apparently some groups are more “democratic” than others, or their “participation” is more desirable. It is commonplace that lower and working class voters turn out in lower percentages than those higher in the scale. This description would fit many Negro voters, such as those in Cleveland. Yet it is not recorded that Bundy’s democratic evangelism has extended to working class Italian and Irish districts, for example. He was not observed to be active in support of the recent campaign of Rizzo in Philadelphia. “Democratic participation” evidently is not the only thing that is desired. As everyone knows, there is a card concealed in the shirt cuff.

- In the fall of 1969, the Ford Foundation helped to finance various school decentralization experiments in New York City. On paper, at least, such decentralization seems to have much to recommend it. Yet in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville district, the teachers felt that Ford money was being used to destroy their union, destroy the laboriously built-up standards of the public schools, and corrupt key members of the Board of Education by giving them “grants.” It may be that school decentralization is desirable. Or the opposite may be true. What is certain here is that Ford money was poured in on whim. “Decentralization” somehow automatically has an appeal; it has an appeal to me; but its concrete effects may be rather different from the idea in the upper middle class mind. Consider this summary by Daniel P. Moynihan:

Seemingly it comes to this. Over and over again the attempt by official and quasi-official agencies, such as the Ford Foundation, to organize poor communities led first to the radicalization of the middle class persons who began the effort; next, to a certain amount of stirring among the poor, but accompanied by heightened racial antagonism on the part of the poor if they happened to be black; next, to retaliation from the white community; whereupon it would emerge that the community action agency, which had talked so much, been so much in the headlines, promised so much in the way of change, was powerless … to bitterness all around.

- The Ford Foundation also put its resources behind “open housing” in the suburbs, evidently deciding on its own hook that integrated living is what people ought to have, whether they want it or not.

- The Ford Foundation put $5 million into a scheme which turns out, on closer inspection, to be a political operation benefiting what can loosely be called a group of Kennedyite political operatives. A product of the merging of three organizations, the Center for Community Change was based in Washington. Its president was Jack Conway, Walter Reuther’s assistant for fifteen years. On its board of directors were: Burke Marshall, a former assistant United States attorney general and a Kennedy functionary; Frank Mankiewicz, Bobby Kennedy’s press secretary and one of the principals in the McGovern presidential organization; Fred Dutton, executive director of the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Foundation, and another McGovern functionary; and the Rev. Channing Phillips, a supporter of RFK, and, titillatingly, the signer of a statement suggesting that the murder of a white policeman by black citizens was “justifiable homicide.”

- Making its way even further out and into the fever swamps, the Ford Foundation supported a variety of extremist groups, regardless of their impact on a local community. Representative Henry Gonzalez, for example, a liberal Texas Democrat, revealed that the Ford Foundation contributed $630,000 to an umbrella organization which then channeled the money to such groups as MAYO (Mexican American Youth Organization). Gonzalez said that members of MAYO traveled regularly to Cuba and distributed pro-Castro propaganda among Mexican-Americans in Texas. The president of MAYO, Jose Angel Gutierrez, spent his time making speeches denouncing “gringos” and calling for their elimination “by killing them if all else fails.” Gutierrez was also on the payroll of the Mexican American Legal Defence Fund (MALDF), which, as you might expect, received $2.5 million from Ford. According to Representative Gonzalez, MALDF offices in San Antonio were festooned with pictures of Ché Guevara.

It is worth pausing here to wonder why Ford finds an individual like Gutierrez so eligible a recipient for its largesse. The answer must be the one discovered by Tom Wolfe in his laughing-through-tears essay “Mau-Mauing the Flak-Catchers.” Wolfe found that officials of the War on Poverty in California tended to regard as most “authentic” those blacks and Chicanos who “Mau-Maued” them—that is, who spouted the most extreme rhetoric, who presented the most exotic appearance, who were, in fact, fountains of anti-white racism. All this validated them as minority spokesmen, in the eyes of white liberals. But, Wolfe also noted, by rewarding extremism—often handsomely—the liberal officials were also helping to create it. When there is a ready market, someone will produce the product.

Ford money in San Antonio also underwrote a vague entity called the Universidad de los Barrios, which was not in fact a university at all, and had no curriculum. In actuality, it was a local gang operation, and the young thugs who were part of it, according to Representative Gonzalez, “have become what some neighbors believe to be a threat to safety and even life itself.” Gonzalez made it clear that all of these Ford-supported extremist groups were loathed by the vast majority of Mexican-Americans.

I have chosen to rely on this Mexican-American example because it will probably not be quite familiar to so many readers. Large chunks of tax-free foundation money have also gone to a variety of black extremist groups; but this is so well known as not to require lengthy discussion.

- The Ford Foundation granted $315,000 to the so-called National Student Association, the title of which is misleading. The NSA was in fact a tightly controlled and self-perpetuating left pressure group about which few students were aware. The Ford grant was supposed to be used for “training schools” where “promising students” [sic] could sharpen their skills in pressing for “curriculum reform” and in “dealing effectively with faculty and administrators.” In other words, and to speak bluntly, the Ford Foundation was putting its money—i.e., tax-free and therefore partially public money—behind the campus revolution.

- For sheer open arrogance, nothing, not even the above, perhaps, can match the Ford Foundation’s grant of $131,000 to eight former aides of Senator Robert F. Kennedy in 1969. Frank Mankiewicz, who got Ford money through the Center for Community Change, got more Ford money through this one: $15,692 for a study of Peace Corps operations in Latin America. Mankiewicz, as previously noted, slid easily off this vacation and into the George McGovern operation. Testifying before Wilbur Mills’ committee, McGeorge Bundy had the effrontery to defend these grants as “educational.” As anyone could see, however, they were really severance pay for benignly regarded political functionaries. Ford money was not bestowed, to my knowledge, on former Reagan or even Humphrey aides.

Let us sum up the argument to his point: At the present time the tax-free foundations represent a conspicuous form of irresponsible power. By this I mean that they can intervene in a variety of ways in political and social matters, and they can do so without any restraining influence by those whom their actions damage. To the above list, many others could be added. And to make matters worse, the activities of the foundations, because of their tax-exempt status, are in a sense partially financed by those whose interests are being damaged.

There emerges from this a political equation of virtually Euclidean clarity. To the degree that the foundations involve themselves in controversial political and social activity, the demand will be raised, and justifiably so, for legislative regulation. Furthermore, the more controversial the activity, the tougher and stricter will be the regulation demanded: and again, in my opinion, justifiably so.

Social Conditions and Foundation Motivation

We have been considering here the manifest desire, yes, the manifestly growing desire, on the part of some of the larger foundations to play an activist role politically and socially, to promote what they euphemistically call “social change.” It is worth asking why this desire has come to the fore in relatively recent years, and whether the assumptions on which it is based are in fact valid. The riot in Watts and, perhaps especially, the riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968 probably had much to do with it. The rhetoric of ethnic suffering, as orchestrated by James Baldwin, Malcolm X and others, which has filtered into the mass media, probably also fuels the desire. Many have drawn the conclusion that the social fabric is in jeopardy, that a national crisis is at hand, and that—something has to be done.

Oddly enough, none of these conclusions seems to be true; at least, none of them is supported by the available evidence. Edward C. Banfield writes:

The plain fact is that the overwhelming majority of city dwellers live more comfortably and conveniently than ever before. They have more and better housing, more and better schools, more and better transportation, and so on. By any conceivable measure of material welfare the present generation of urban Americans is, on the whole, better off than any large group of people has been anywhere. What is more, there is every reason to expect the general level of comfort and convenience will continue to rise at an even more rapid rate through the foreseeable future.

James Banfield.

Banfield goes on to say that “there is still much poverty and much racial discrimination, but there is less of both than ever before.” Conclusions like these, solidly based on empirical evidence, do not support the assumption that the society is in crisis. Banfield further shows that the riots mentioned above had little to do with poverty or absence of opportunity and were not importantly motivated by “racial” feeling. And he shows that the problems that do exist are for the most part highly resistant to infusions of money by government or by the foundations.

And yet, he notices, “Doing good is becoming—has already become—a growth industry, like the other forms of mass entertainment, while righteous indignation and uncompromising allegiance to principle are becoming the motives of political commitment.” It is clearly in the interest of the “growth industry” he designates to define problems as “critical” and to demand the authority to “do something” about them. It is clearly in the interest of that growth industry to claim that unless something is done, disaster will occur.

Here we have, I think, a clue to the syndrome that afflicts those who evangelize for social activism in the world of the foundations. Against all objective evidence, they exaggerate the seriousness of our various social difficulties. They falsely suggest, and may even believe, that the activities they propose and sponsor will ameliorate those difficulties—though the reverse is more often the case. And it certainly pleases the ego of the foundation functionary to feel that he is coping with vast crises and apocalyptic dangers, as well as dealing with exotic types from the ghettoes and barrios. But it seems to me the more prosaic truth is the one articulated by Edward C. Banfield in the conclusion of The Unheavenly City:

The import of what has been said in this book is that although there are many difficulties to be coped with, dilemmas to be faced, and afflictions to be endured, there are very few problems that can be solved; it is also that although much is seriously wrong with the city, no disaster impends unless it be one that results from public misconceptions that are in the nature of self-fulfilling prophecies.

The conventional rhetoric of crisis, from that perspective, is not at all part of the solution, but a principal source of the problem, for it perpetuates a veritable reign of error.

Knowledge and Beauty

The pity is that the foundations, for all their social activist fancies, do have an important role to play in our society. And there follows from the above discussion a clear recommendation, i.e., that the foundations concern themselves with activities that will be perceived as beneficent by all segments of the national community. Indeed, so far as I can see, the tax-exempt status of the foundation enjoins them to pursue such a policy.

To be sure, the foundations have long supported scientific endeavor. No segment of the community is likely to object to the use of tax-exempt funds for cancer research or research into heart disease, nor is anyone likely to find it anything but praiseworthy for the foundations to support attempts to discover through experimentation better methods of giving instruction in reading or arithmetic. The social sciences also afford a wide range of possibilities for the use of tax-exempt funds in ways which will benefit the entire community. This first recommendation, for the support of the sciences and social sciences, might be termed the case for disinterested—but not, therefore, frivolous or useless—knowledge.

Knowledge, disinterested knowledge, is surely one entirely noncontroversial good. Even a little knowledge is not a dangerous thing; though, as Pope said, a little learning may well be. But there in another disinterested good, complementing Knowledge, and it is the basis for my second recommendation. If the scientific pursuit of Knowledge has broad claims, so too does the creation of Beauty. One thing that has struck me forcibly about the foundation world is its obsessive and oppressive moralism. Foundation people, as I meet them—and it must by now be obvious that I meet them as a kind of anthropologist amidst a strange tribe—tend to be interested in what is immediately useful, as they conceive of it, and what is morally good, as they conceive of it. There is an immense irony here, from the standpoint of the cultural anthropologist. Many in the foundation world, especially among the activists and reformers, think of themselves as critics of society and agents of change. Yet in nothing are they so continuous with previous American culture as in their moralism and utilitarianism. Their spiritual ancestors were freeing the Negro; they are still freeing the Negro. Their spiritual ancestors were packaging breakfast cereals or making Model Ts: they are still, though less usefully, fiddling with the nuts and bolts of society. Like the nineteenth-century millionaires whose money they are now spending, these twentieth-century reformers are moralists and utilitarians, civilizationally speaking brothers under the skin to Ford, Kellogg, Carnegie and all those other flinty, moralistic, but not especially civilized types.

I would now like to present my second proposal. It is serious intellectually, and serious in the sense that I would like to see it come to pass; but not serious in the sense that I expect it to come to pass.

I would like to see some powerful corrective to our pervasive moralism and utilitarianism come into existence in America. Will the puritans and the mechanics, in their latter manifestations, never stand down—even when they are doing no demonstrable good? I think it might generally be perceived as a benevolent and disinterested good if the foundations summoned the courage to behave like Florentine Medici of the Renaissance Popes. The creation of beauty, after all, is a function of status and luxury; the Sistine Chapel was not conceived of in a spirit of utilitarianism or moralism. And, after all, things like the Ford Foundation, and the others, are creatures of status and luxury.

The Sistine Chapel. License: Wikimedia Commons.

It is also true that to bring about the creation of beauty a great deal of money may have to be wasted. Not every Renaissance artist was a Michelangelo. But the foundations would seem to be in an ideal position to do this. In fact, they are wasting a great deal now. And I would urge that they shift a good deal of their expenditure to the arts, cast their bread (no pun intended) upon the waters, in support of painting, architecture, music, and so on. Not just a piffling amount, either: at least a couple hundred million—as befitting the modern equivalent of a tax-free Renaissance prince. Beauty, like Knowledge, is not divisive. It is a disinterested value. It shines on all alike. And if the foundations supported not only science, which is universal, but also aesthetic endeavor, which is universal too, perhaps with a little luck this civilization will make some permanent contribution to the human spirit and be interesting to people five hundred years from now.

***

In a brief, three-paragraph Addendum at the end of Hart’s chapter in The Future of Foundations, he takes the opportunity to respond to another chapter in the volume by Yale professor John G. Simon, whose contribution offered a defense of foundations’ liberal political and social initiatives. “In general, I prefer to let the two essays speak for themselves,” according to the Addendum, in which Hart also notes, “A careful reading of the ‘cautionary guidelines’ set forth at the end of his essay, however, suggest that we may in fact be more in agreement than would be gathered from the rest of his essay.”

This article first appeared in the Giving Review on February 18, 2025.