Nostalgia fuels populism across the political divide. When times are tough, such as during the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, populist rhetoric offers emotional solace through promises of economic restoration. Yet policymakers must maintain their forward gaze when thinking about workers. A more prosperous American future will emerge only through productivity-enhancing innovation and by empowering the US labor force with the adaptability required in a dynamic, high-octane economy.

To attempt otherwise is futile. As noted in the new Wall Street Journal piece “How the U.S. Lost Its Place as the World’s Manufacturing Powerhouse,” the dramatic drop in American manufacturing jobs—falling from 35 percent of private-sector employment in the 1950s to just 9.4 percent today—reflects a fundamental economic transformation (including increased automation, a spending shift from goods to services, and, yes, changing trade patterns) that can’t be reversed. Protectionist policies certainly have proven ineffective. Indeed, Trump Trade War 1.0 likely reduced manufacturing employment.

And consider the impact on non-manufacturing employment from tariffs, via Goldman Sachs:

The broader statistical evidence points to negative net employment effects. While the range of estimates is wide, academic studies generally find that a 10pp increase in tariff rates raises employment in protected industries by 0.2-0.4% but that each 1pp increase in tariff-driven costs lowers employment by 0.3-0.6%. Scaling these estimates to the US economy imply a boost of just under 100k to manufacturing employment from tariff protection but a roughly 500k drag on downstream employment from input cost pressures.

Anyway, the manufacturing nostalgia misunderstands America’s economic evolution. Though manufacturing employment has decreased, output just keeps on growing. American factories now produce higher-value goods at better wages with fewer workers—and more robots. For value added per worker, American manufacturing leads major economies, with productivity estimated at nearly seven times China’s, according to “Nostalgia for manufacturing will make the US poorer” in the Financial Times.

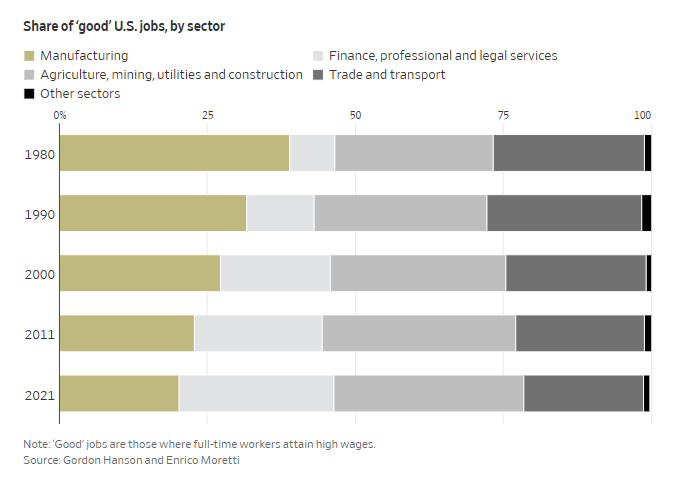

That piece also notes that since 1990, America has gained 11.8 million positions in professional and business services and 3.3 million in logistics tied to global supply chains—easily offsetting five million lost manufacturing jobs. The WSJ makes a related point about what jobs pay: In 1980, manufacturing accounted for 39 percent of the US jobs where workers earned high wages. By 2021, that had dropped to 20 percent. Meanwhile, the share of high-paying jobs in the finance, professional, and legal industries jumped from eight percent to 26 percent.

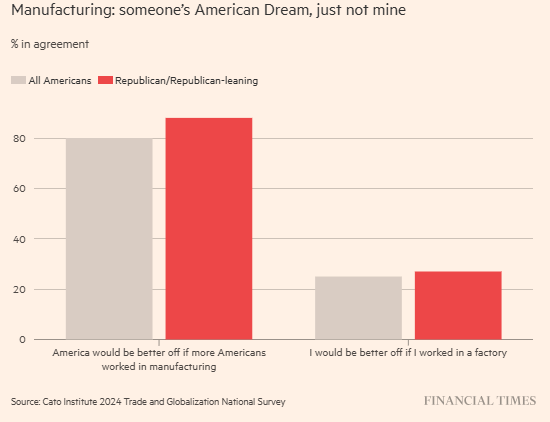

Then there’s this: Americans themselves show little enthusiasm for factory work. “Manufacturing jobs for thee, service jobs for me,” I guess.

Reality-based economic policy would recognize the aforementioned data. Rather than costly and ineffective protectionism, better approaches include targeted retraining, mobility assistance, and reducing regulatory barriers to both labor market flexibility and the ability to build infrastructure in a timely and cost-effective way.

If you’re thinking about the future of US manufacturing, consider this news, which just dropped today, via Barrons:

Nvidia said on Monday it plans to build AI supercomputers in the U.S. “The engines of the world’s AI infrastructure are being built in the United States for the first time,” Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang said in a press release. “Adding American manufacturing helps us better meet the incredible and growing demand for AI chips and supercomputers, strengthens our supply chain and boosts our resiliency.” Nvidia said it would use artificial intelligence and robots to automate its manufacturing operations in the U.S.

The post Innovation, Not Nostalgia, Will Power the Future of US Manufacturing appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.