Hello and happy Sunday.

For years Syrians have suffered strife and war, with the myriad religious and ethnic groups that call it home divided. With the fall of the regime of dictator Bashar al-Assad —the source of much of that division—in December came hope that the country could once again unite in spite of those differences. But perilous questions lie ahead, evidenced by recent clashes that have left hundreds dead.

In this week’s Dispatch Faith, journalists Joseph Roche and Iryna Matviyishyn report from Homs, Syria, on the role many Christians feel responsible to play in Syria’s future. Though they fear sectarian violence and perhaps even religiously motivated discrimination by a new Islmist government, their focus is on uniting Syrians of various religions and ethnic groups—come what may.

Joseph Roche and Iryna Matviyishyn: Between Fear and Reconciliation in Syria

HOMS, Syria—In the courtyard of a Jesuit church in central Homs—located between Damascus and Aleppo—about 30 people listen attentively to representatives of the three main faiths represented in Syria—Christians, Alawites, and Sunni Muslims.

Homs, once nicknamed the “Capital of the Revolution,” is now merely a shadow of its former self. Besieged by former President Bashar al-Assad’s forces and the Russian Air Force from 2012 to 2014, it became a martyr of a city. The name reflected both its devastation and its role as an early stronghold of resistance in Syria’s yearslong civil war. One of the first cities to rise against Assad in 2011, Homs faced brutal retaliation, with relentless shelling and starvation tactics aimed at crushing the rebellion. Today, it is little more than a heap of ruins, where a scattered population of survivors navigates the devastation.

Homs is a microcosm. The fall of Assad’s regime three months ago has left behind a fractured Syria, inflamed by decades of divisive politics. Matah al-Hussein, one of the participants at the church discussion, belongs to the Alawite minority—the heterodox branch of Shia Islam from which the Assad family hails and upon which the architecture of his regime was built.

“The government made sure that each person stayed in their own neighborhood and did not interact with others. The 14 years of war only reinforced this division,” al-Hussein, a young art student, said. “For example, the Hamidiyeh district is very Christian, but if you walk for 10 minutes, you arrive in an Alawite neighborhood—each community has its own armed group for protection.”

But that began to change in early December. It was then that fighters from the HTS (Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) group—a movement that emerged in 2017 in Idlib (northwestern Syria) from a merger of Islamist and rebel factions—launched a lightning offensive on Damascus. In less than two weeks, it put an end to 52 years of dictatorship. The first weeks afterward were marked by a general euphoria, with celebrations filling the streets to mark Assad’s departure. But since then, Syria has been haunted by its old demons.

Earlier this month, reports surfaced of violent crackdowns by Syria’s new Islamist rulers in the Alawite region of Latakia, resulting in over 1,000 deaths, including 745 civilians. While most of the victims were Alawites, Christians were also reportedly caught in the violence. The attacks have intensified fears among Syria’s Christian communities, prompting mass evacuations and raising concerns about their safety under the new regime.

“Many towns, villages, and neighborhoods have seen their homes burned and looted,” Patriarch John X of the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch said in remarks addressed to interim Syrian President Ahmed Hussein al-Sharaa. “The targeted areas were Alawite and Christian communities. Many innocent Christians have been killed.”

Yet even with fear about the future, many of Syria’s Christians seem intent on finding ways to bind the wounds of Syria’s diverse communities of religions and people groups—so long used fractured by decades of tyranny.

Living together.

At the foot of the central clock in Homs, armed HTS men take turns posing for photos, one finger pointing toward the sky. Flags of the Syrian Republic flutter over administrative buildings that once belonged to the regime, while on the ground, passersby unknowingly trample old posters bearing Assad’s image.

Yet in the Christian district of al-Hamidiyah, feelings of fear and hope clash in turn. Before the war, the city was home to nearly 125,000 Christians—about 10 percent of the city’s population—mostly Orthodox (Greek and Syriac), but also Catholic communities and a minority of Protestants. Today, while many celebrate the fall of the Assad regime, they remain cautious about Damascus’ new government and worry about their future. For now, as the Syriac archbishop of Homs, Monsignor Jacques Mourad insists that the focus must be on reconciliation among all groups in Syria.

“The liberation I felt on December 8 was like a rebirth—both for me and for the entire Syrian people,” he said. “For the first time in my life, I could finally breathe what it means to be free. No one expected the regime to fall. It’s a beautiful and great surprise.”

Sister Rania Hanna is still struggling to believe that Assad is gone. “We all welcomed his departure with immense joy and hope,” she said. “The Assad family took us Christians hostage, using us as a façade to justify their war against the Syrian people.”

For decades, the Assad regime presented itself as the protector of minorities, particularly Christians, in a region plagued by instability. Yet, according to Hanna, this so-called protection was nothing more than a smokescreen. In reality, she explains, Christians were often exploited to serve the regime’s propaganda, which sought to justify its brutal repression by portraying a “civilized” front against an opposition it labeled as terrorist.

“But the truth is that most Christians opposed Assad—or at the very least, refused to take sides in the war,” Hanna said. “Many of us fought against the regime. A great number of Christians paid with their lives, dying under Russian bombs or in the regime’s prisons.”

Her gaze heavy with sorrow, Hanna surveyed the labyrinth of the Christian quarter, taking in the vastness of the piles of rubble the crumbs of what used to be buildings. With a sigh, she adds:

“Ten years after the siege ended, nothing has ever been rebuilt,” she said. “The government never gave us a single cent. Everything we have rebuilt, we owe to Christian charity.”

The fear of tomorrow.

In his office in the Hamidiyeh district, Monsignor Mourad, his round face beaming with a warm smile, sits near a stove for warmth as he pours coffee into small porcelain cups. “In general, when HTS launched its offensive [against Damascus], Christians were afraid—we feared another war would break out,” he said. “As a result, many left the city. But what’s touching is that the day after the liberation, they all returned to Homs because, for the first time in a long while, they felt safe.”

Yet, he acknowledges that the situation has since deteriorated, and in the prevailing chaos, a threat against Christians could emerge.

A former hostage of ISIS, Mourad takes seriously the fears of Syria’s Christians regarding HTS, a group with a troubled Islamist past that evolved from Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s former affiliate in Syria. While HTS has attempted to rebrand itself as a local Syrian force with governance ambitions, it remains designated as a terrorist organization by the European Union and the United States due to its extremist origins and activities. Controlling parts of Idlib province, the group enforces a strict interpretation of Islamic law, fueling concerns among religious minorities, including Syria’s Christians.

Since the fall of Assad, Mourad has repeatedly stated that no deliberate violence has been committed against Christians in Syria. However, since the violent clashes of March 2025, he has expressed growing concern that the country is once again descending into a spiral of conflict.

“There have been no violent acts against Christians, and Ahmad al-Sharaa has met with us, assuring that he will do everything to guarantee our religious and cultural freedom,” Mourad told his community soon after the new regime took power. Yet, he does not deny that some members of the Christian community were arrested by HTS forces. He insists, however, that these arrests were not based on religious affiliation but rather on the individuals’ active roles within and collaboration with the Assad regime.

Following this month’s sectarian clashes between Alawites and Sunnis in the Latakia region, Mourad continues to argue that Christians are not being targeted for their faith but, like all Syrians, are caught in the crossfire of broader violence. “This violence affects the entire Syrian people,” he said. “It is primarily directed against Alawites, but Sunnis, Ismailis [a branch of Shia Islam], and Christians have also suffered. When violence erupts, it spares no one.”

He further clarified: “Christians were killed, not because they were Christian, but because they lived in Alawite neighborhoods. They were collateral victims.”

Hanna, also positive about al-Sharaa, is primarily concerned about his ability to control all the factions that now make up his ruling coalition. “There are many different groups within HTS. Some are more religious than others,” she said. “That’s also why a majority of us fear the Islamization of Syria. For instance, armed men sometimes ask women to wear veils or to sit separately from men on buses. Many Christians say that if the government radicalizes and becomes fanatical, they will have no choice but to take the path of exile.”

Mourad hopes the new government will protect Christians as well as other minorities: “If I am protected but my neighbor is not at peace, it will not work. We want a country where we all live in peace—because we have seen far too much blood.”

‘A bridge of reconciliation.’

Father Tony Homsy leaned forward, his hands clasped as if holding the weight of his words. He had no illusions about the difficulty of the task ahead. Reconciliation in Syria would be neither easy nor immediate. But for him, it was necessary. More than just a conversation, the gathering at the Jesuit church in Homs was an attempt to break through the hardened walls of mistrust between Syria’s Christian, Sunni, and Alawite communities. It was a space where grievances could be aired, anger acknowledged, but also where dialogue, mutual respect, and the first fragile steps toward healing could take root. The goal was not to erase the past but to find a way beyond it—to build, together, a Syria that belonged to all.

Homsy’s greatest concern, however, was not for his own community, but for the Alawites. “The Sunnis were the regime’s first victims,” he said, his voice steady but heavy with meaning. “Many of them, understandably, want revenge against the Alawites, whom they sometimes—rightly or wrongly—associate with Bashar’s regime. As Syrian Christians, our duty is to be a bridge of reconciliation between these two communities.”

Across the courtyard, al-Hussein, the Alawite, listened intently. He had come to this discussion with cautious hope, but to him, this kind of initiative was not just important—it was vital. “Today, we must break this cycle of violence by encouraging communities to meet and realize that we are all human beings, just like everyone else,” he said.

Yet, as Homsy admitted, hope alone would not be enough. His gentle gaze, framed by small round glasses, carried the quiet weight of a man who had seen his country fracture. He knew that moving beyond divisions required more than goodwill—it demanded courage. For him, Syria’s survival depended on rejecting the ethnic and religious boxes that had been used to pit its people against each other. “We must recognize that we are Syrians before anything else,” he said.

He did not hesitate to challenge his own community. “Christians must stop hiding behind their identity and instead act as true Syrian citizens,” he insisted. “They should not seek only their own security but also defend the rights of all and remain faithful to the prophetic message that proclaims that everyone is precious in the eyes of God.”

For Homsy, Christianity in Syria could not be about self-preservation. It had to be about building bridges—borrowing the words of Pope Francis—not walls. But he also knew that reconciliation could not mean forgetting. “The real challenge, in my view, is to find a way to forgive without erasing the past—to remain honest while conveying a message of love and brotherhood,” he said. “This message of peace and unity is precisely what Syria’s Christians can bring.”

Valerie Pavilonis: MoMA Goes to Hell

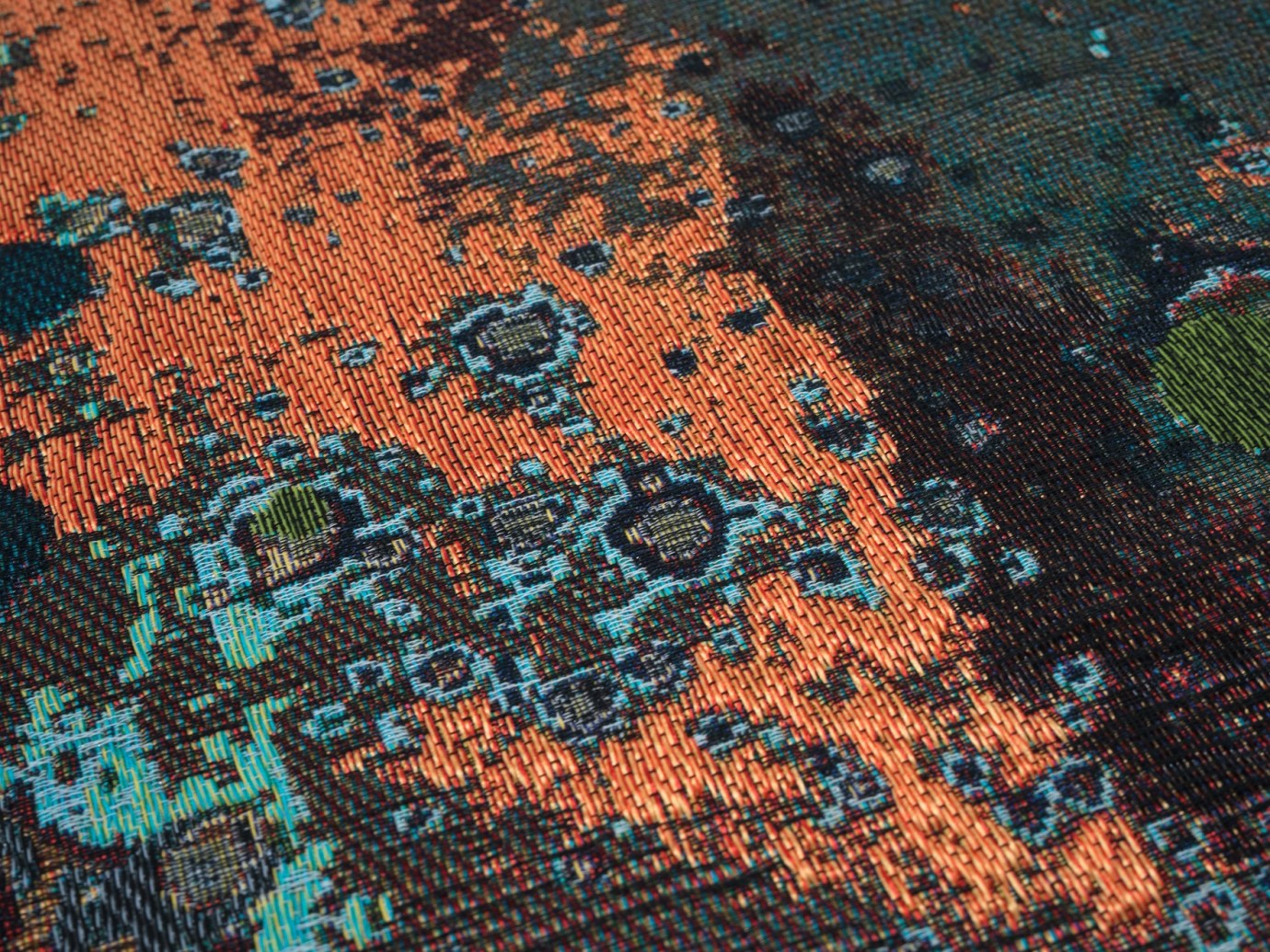

A recent trip to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and for Dispatch ideas editor Valerie Pavilonis led to some provocative observations about the human body, art, and hell while pondering a tapestry: Cadence by Otobong Nkanga.

t’s a richly colored work with explosive patterns, but what I noticed most viscerally was the biology: What look like arteries and bronchial tubes float in dusky blue, and two human figures, male and female and mostly rendered via circulatory systems, observe from the center of the landscape. And running the length of the tapestry is a thin network of blue veins. If someone told me that The House of Hades inspired Nkanga to make this work, I would totally believe them.

This is unlikely, and the plaque associated with the work, called Cadence, uses phrases like “states of censorship and visibility,” and “social and ecological turmoil.” (If you can intuit these things from the work without looking at the plaque, you’re smarter than me and can have my job.) But whether the artist intended it or not, there’s something hellish about Cadence—and I think that’s a good thing.

I find that art, particularly modern art, is a useful stretching mechanism, one that can take us outside our perceptions and probe our depths a little bit more.

This is not to say that art is divine. But God speaks, and has spoken, through the senses. Taste is one: Jesus turned water into wine. Smell is another: the bush may not have burned, but fire still stinks. Sight is yet another: Saul saw a bright flash before he went blind. And of course, the ultimate example: God’s slain son, maimed on a cross, dripping water and sweat. Women sobbed, soldiers wiped their bloody hands, and at 3 o’clock sharp the light left the sky. There was no letter that drifted slowly from the heavens, however miraculously it would have been, that simply stated: Follow me. Those words were instead etched not on paper but on memory.

We are not just thought-to-text machines; we are embodied for a reason. There is so much to creation, and by extension, human life, that is more than words or pictures right in front of us.

Read the whole thing on our website.

The Dispatch Faith Podcast

Religious freedom advocate Nadine Maenza was on the ground in Syria less than a month ago talking with Christian leaders and government officials about the country’s future. She joined me on this week’s Dispatch Faith podcast to discuss whether the transitional government can truly unite the war-torn country. Maenza is president of the IRF Secretariat, a non-governmental organization focusing on building the religious freedom movement globally. She previously served two terms on the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, including one term as its chair. These weekly conversations with Dispatch Faith contributors are available on our members-only podcast feed, The Skiff.

More Sunday Reads

- As the monthlong fast of Ramadan continues until nearly the end of March, Fiona André reported for Religion News Service on a group of American Muslims having trouble adhering to their religious beliefs: those in prison. “Prisoners who observe Ramadan, who don’t take any food or water between sunrise and sundown, are often forced to break their fasts when eating is not officially permitted, or are not allowed to congregate for Eid al-Fitr, the celebration marking the end of the holy time. Instead of growing spiritually, many prisoners spend the month engaged in tedious legal battles to ensure their religious rights are respected. The Council on American-Islamic Relations, the nation’s largest Muslim advocacy group, sees a spike in the number of complaints filed by inmates. Most of these cases arise because of lesser consideration given to non-Christian inmates, out of ignorance and sometimes bigotry, said Corey Saylor, a research and advocacy director with CAIR.” What might help, André writes, is more Muslim prison chaplains. “Salahuddin Muhammad, vice-president of the corrections department for the Association of Muslim Chaplains, said potential candidates shy away from joining the chaplaincy because of notions that serving imprisoned people is unsafe. Muhammad primarily works at FCI Butner, a federal correctional complex in North Carolina where he mediates between the prison staff and inmates. During Ramadan he often has to remind staffers of their obligations about inmates’ religious rights, while negotiating matters such as whether inmates with medical conditions can fast despite the facility’s medication schedule interfering with fasting hours. ‘In Islam, we have concessions, if you have an illness, you don’t have to fast. So I talk to them about that, that’s probably the biggest thing during the month of Ramadan,’ he said.”

- At First Things, Jacob Akey wrestles deeply with the best way to help the homeless, and how material-centric approaches are often lacking. “Pope Francis, for his part, offers actionable advice: ‘Give without worry.’ The Holy Father, and those who echo his advice, emphasize personal charity and the how of giving—’stop, look the person in the eyes, and touch his or her hands.’ The Church has consistently taught that the answer to the question of personal giving is ‘Yes, and more.’ At the same time, however, calls for unqualified giving to the street homeless evince an unreality. Pope Francis asks that, in our giving, we not concern ourselves with what the money is used for. Who are we to judge if a homeless person wants to buy ‘a glass of wine’? On a Coney Island F Train, just before Christmas, Sebastian Zapeta-Calil killed a woman by setting her on fire. Zapeta-Calil would, according to an acquaintance, daily descend into an alcohol and synthetic cannabinoid-fueled psychosis. One wonders at the ethics of funding his ‘glass of wine.’ Homeless advocates, secular and religious, seem stuck in the belief that street homelessness is a primarily material problem—enough money will solve it. And, while the high cost of housing is itself a problem, it was not Ramon Rivera or Sebastian Zapeta-Calil’s problem. It is not the problem of the men I see daily. Theirs is a soul sickness. But so long as those who address homelessness do so on strictly material terms, they will lack not only the tools to help the homeless but the tools to help the rest of us, too.”

A Good Word

Earlier this week, many Jews celebrated Purim, the holiday commemorating the events described in the book of Esther, in which she saves her people from genocide. Two stories from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on Purim celebrations in Israel caught my eye this week. The first, reported by Deborah Danan, begins: “Welcoming children for a Purim celebration this week, the security guards at the official home of Israel’s president drew laughs when they asked a routine security question: Was there any metal in the children’s costumes? These weren’t typical visitors. The children wore a costume designed around their mobility device – wheelchairs and walkers transformed into rockets, game consoles, and circus tents. Yes, there was metal inside. Hosted by First Lady Michal Herzog, Monday’s event marked the 10th anniversary of an initiative that creates custom Purim costumes for children with disabilities. Organized by Beit Issie Shapiro, a nonprofit focused on disability inclusion, the project paired dozens of children with professional designers from the Holon Institute of Technology and, for the first time this year, website builder Wix.” And the second, by Philissa Cramer, begins: “For a year and a half, a photograph of the Bibas family wearing Batman pajamas served as a symbol of the global vigil for their return from captivity in Gaza. Batman was a passion for Ariel, who was 4 when he and his family were abducted from their home in southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023. He had dressed as the superhero for Purim that year, and his parents, Shiri and Yarden, were happy to buy matching gear for the entire family, including his new baby brother Kfir. Now, on the first Purim since Shiri, Ariel and Kfir were confirmed dead and returned to Israel for burial — and with Yarden back in Israel after a hostage release last month — Jews around the world are dressing as Batman in their honor. In Israel, entire classes of schoolchildren have worn orange Batman capes and masks, in a nod to both Ariel Bibas’ passion for the superhero and the brothers’ red hair.” Cramer included a message from the Bibas family: “‘Time after time during the last almost year and a half and especially during the last few weeks, you have shown us that Ariel and Kfir will never leave us.’”