Recent tariff-related turmoil in the U.S. stock market has motivated several Trump administration officials and many of their online allies to shrug it off as unrepresentative of the “real” U.S. economy. Many have argued, in fact, that the scary sell-off of U.S. stocks, bonds, and dollars—one that abated only after Trump pulled back from the tariff abyss last week—was not just meaningless “digital ones and zeroes” but actually good because “Wall Street” losses meant “Main Street” gains. In one narrow sense, the tariff lovers have a point: Day-to-day fluctuations in certain stocks and even entire indices are often disconnected from what’s going on at, say, your local bar down the street. In a broader sense, however, the idea that recent market troubles aren’t related to the “real” U.S. economy or, even worse, that what’s good/bad for “Wall Street” is necessarily bad/good for “Main Street,” is absurd. And populists peddling such myths are either clueless about what the stock market is or are simply desperate to avoid admitting that Trump’s tariffs are harming both it and the “real” U.S. economy more broadly.

The ‘Wall Street’ Basics

For starters, publicly listed companies in the United States are themselves major contributors to the U.S. economy. As of last year, there were about 4,300 U.S. companies traded on various U.S. stock exchanges, representing 11 sectors and dozens of industries. These firms include not only tech behemoths and big investment banks, but also many small and medium-sized American companies in “blue collar” industries such as energy, materials, and manufacturing. Those firms, for example, are collectively about 25 percent of the Russell 2000 index, which contains only companies with a market capitalization of less than $2 billion (and is down more than 20 percent since mid-November). For comparison, Apple’s market cap is $3 trillion—i.e., more than a thousand times the size of the biggest Russell 2000 company.

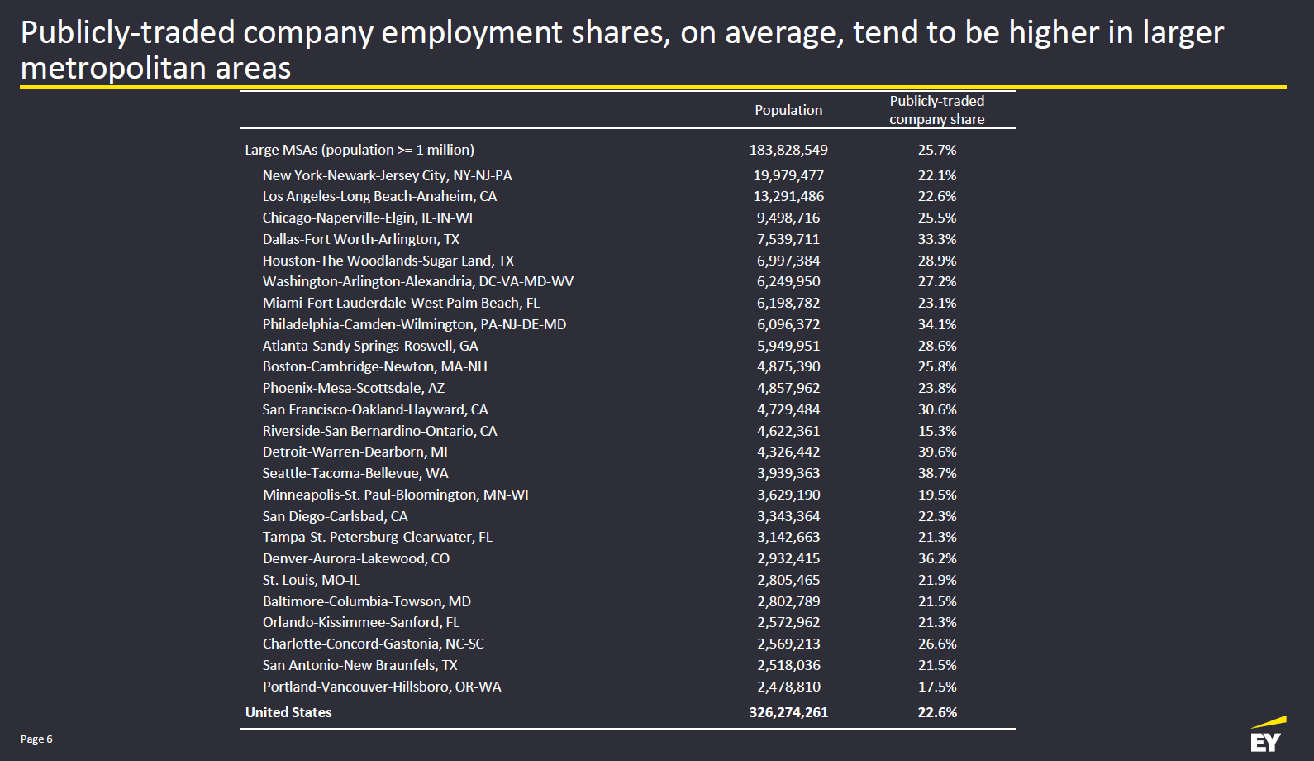

Altogether, publicly listed companies employed around 28.3 million people (23 percent of the U.S. workforce) last year. In certain large metro areas like Detroit, Seattle, Denver, and Dallas, however, the share of Americans working at publicly traded firms is much higher, topping out at almost 40 percent in top-dog Detroit:

Since public companies tend to be larger, they also constitute a huge portion of the United States’ economic output. Over the last 12 months, for example, total revenues of public companies in the United States exceeded $22 trillion, and it’s estimated these firms account for approximately half of U.S. GDP—around a quarter directly and another quarter indirectly through investment, lending, innovation, wages, and other business activities (though precise estimates are difficult). Public firms are also disproportionate contributors to U.S. business capital spending (around half in 2019), and their local performance can spill over into neighboring regions. And while the total number of public companies has declined significantly since the 1990s, their contribution to GDP and employment has remained steady.

A big drop in a company’s stock price can mean less available capital for funding operations, expanding the business, hiring workers, or paying off debt (equity is one way to finance business operations). It’s also a signal that outside investors—many of whom are trained to evaluate a company’s health and future performance—think it’s in for rough times ahead. And both of these things, in turn, can deter other investors, lenders, and market players from doing business with the firm in the future. All of that is bad for the company and the people who work there.

‘Wall Street’ and Everyday Americans’ Wealth

Then, of course, there are the market’s contributions (pun!) to Americans’ wealth and financial security. As of 2024, more than 41 percent of American households’ financial assets were tied to the stock market—a new record high—while approximately 62 percent of all U.S. adults had investments in individual stocks, mutual funds, and retirement savings accounts like 401(k)s and IRAs:

This number, moreover, likely understates how many Americans actually have some kind of stock market exposure, whether directly or indirectly. For example, approximately 15 percent of private employees, 85 percent of state and local government employees, and almost all federal employees have access to a defined benefit pension plan that’s at least partly invested in the market. Given the way Gallup worded the question above, it’s all but certain that many people with pensions aren’t in the 62 percent figure, thus making the real number of Americans invested in the market even higher.

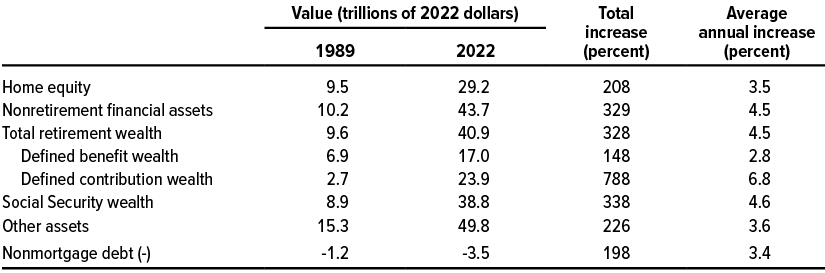

While daily market fluctuations may fund the lifestyles of professional traders and meme-stock novices, other Americans’ market exposure over the longer term—in both retirement and non-retirement financial assets—has been a major contributor to increased wealth and financial security. As we discussed a few weeks ago, in fact, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently calculated that U.S. household wealth hit an inflation-adjusted record in 2022 (the most recent year available):

Not all these wealth gains came from the stock market, but—as shown above—many of them did. And the overall wealth created by “Wall Street” has been nothing short of breathtaking. As one recent paper calculated, “US stock market investments increased shareholder wealth on net by $47.4 trillion between 1926 and 2019.” Given the last several years of market outperformance, that already-mind-boggling number is surely even higher today (even with recent tariff-related declines).

The gains, of course, inevitably come with losses, too—ones that can be exacerbated by big, short-term market swings and good ol’ human nature. As Politico reported this week, for example,

[S]ome people in the financial world are suggesting that administration officials are missing the point when they say they’re more concerned about Main Street than Wall Street. Between pension funds, the hordes of investors holding exchange-traded and mutual funds and the pack of individual “meme stock” investors, there are plenty of everyday Americans dealing in the stock market day in and day out. And while many are holding on for the long-term — that is, if they’re following the advice of most investment pros — the market’s wild swings are clearly causing concern: A survey last week from CNBC and SurveyMonkey found that 41 percent of Americans with investments have changed their investments because of the tariff-induced volatility.

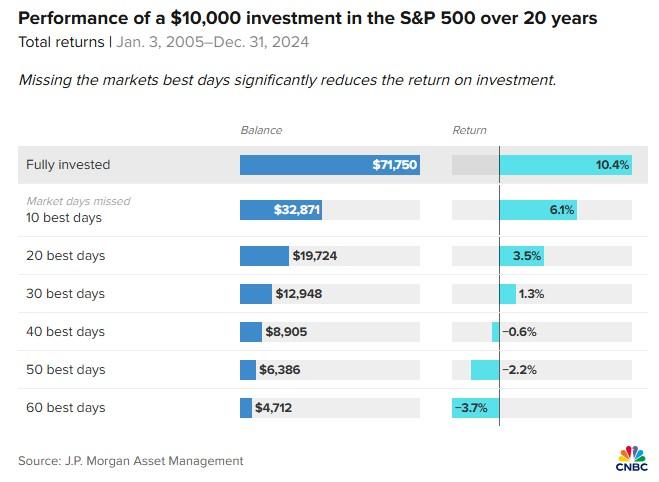

As a recent analysis by JPMorgan shows, these kinds of (understandable!) jitters can mean big losses in Americans’ long term wealth because some of the market’s best days come shortly after its worst. Thus, getting out of the market for just a few days can mean huge differences in wealth over the long term—or even losses:

It might be easy for younger, savvier investors to ignore recent market gyrations, but the same can’t be said for millions of Americans nearing retirement, currently relying on dividends, watching their college-aged kids’ 529 accounts shrink, or in similar situations. For many of them, the market’s recent declines will matter.

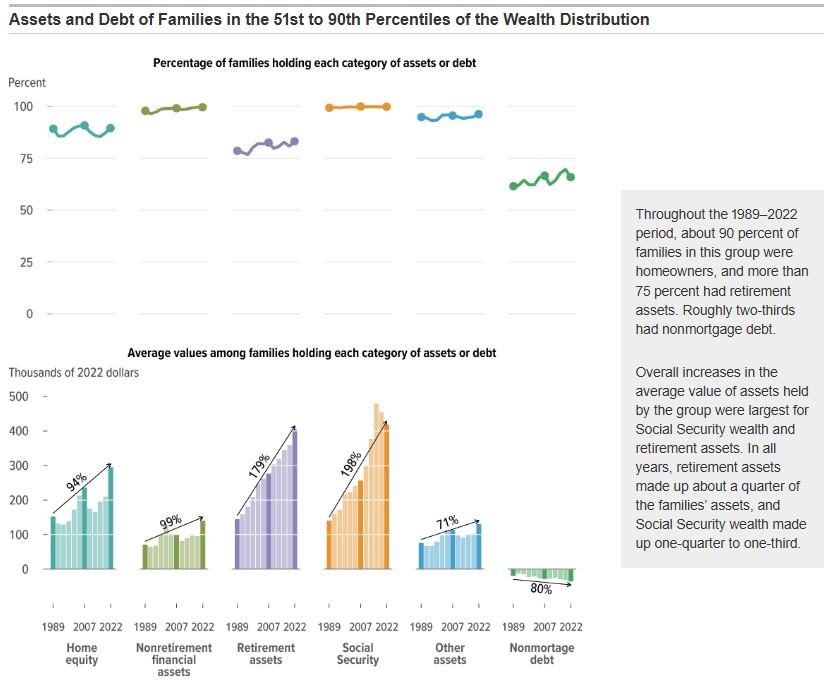

Granted, a lot of the wealth created by the stock market was experienced primarily by richer Americans, but this fact shouldn’t be oversold. For starters, the CBO household wealth data show that most of the American families in the 51st to 90th percentiles of the wealth distribution—so, doing above average but not mega-rich—had financial accounts during the period examined and enjoyed major gains therein:

Poorer Americans also have some market exposure: About one-half of U.S. households in the 26th to 50th percentile and one-third in the bottom 25th percentile had had retirement accounts during the period CBO examined—shares that had increased significantly since the 1980s.

Furthermore, financial market performance can indirectly affect Americans who aren’t invested themselves. The market for U.S. government debt, for example, is closely linked to mortgage rates, so “when Treasury yields rise, borrowing becomes more expensive — potentially leading to higher monthly payments for those taking out new mortgages.” Auto loans, credit cards, and other forms of consumer credit react in a similar fashion.

So-called “paper wealth” can also affect American workers in other ways. The Wall Street Journal reports, for example, that wealthier Americans have accounted for an increasingly large share of all consumer spending because swelling home values and stock market portfolios gave them the security and confidence to splurge more today—supporting other Americans’ jobs and the economy more broadly. Thus, “[a] stock market selloff or decline in home values that rattles the confidence of the top 10% and causes them to cut back would have a significant effect on the economy”—one that goes way beyond just the wealthiest Americans’ portfolios.

‘Wall Street’ as an Economic Barometer

Finally, the stock market is a barometer—albeit an imperfect one—for U.S. economic conditions, including those on “Main Street.” In general, most stock prices rise when investors expect stronger economic growth, which can fuel consumer spending, corporate earnings, and business expansion or new investment. Those expectations, in turn, are driven by a boatload of traditional and nontraditional data at the company, industry, regional, national, and global levels, as well as the actions and statements of influential entities like the Federal Reserve and (as recent tariff mayhem has shown) the White House. So, for example, when big banks reported earnings this past week, investors were already looking ahead to a possible U.S. recession on the horizon, thanks at least in part to Trump’s tariffs, which would increase the banks’ credit and lending risks (e.g., borrowers’ inability to repay loans) or decrease their revenue (e.g., borrowers’ reducing capital expenditures or paying off loans early). Big swings in the market can also affect consumer sentiment and thus feed into real economic conditions as we cut back on spending in advance of an expected downturn.

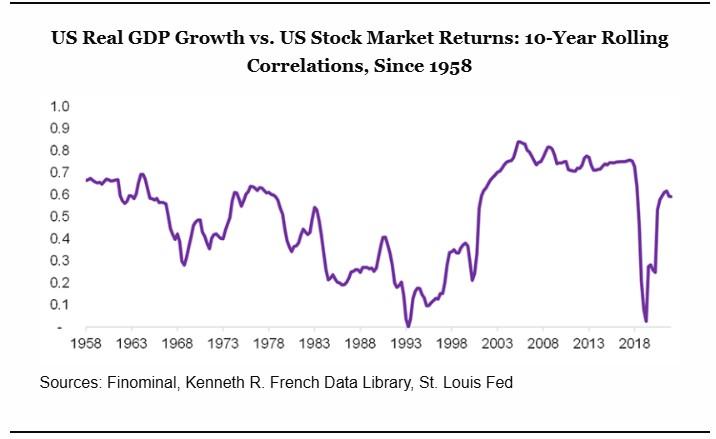

In the short term, of course, U.S. stock market performance doesn’t necessarily mirror the U.S. economic real world, and things can certainly go haywire during events like the Great Depression or the pandemic. Over longer periods, however, the stock market’s performance has a significant historical correlation with numerous real-world economic indicators, such as GDP, investment, and industrial production. As one recent analysis put it, “the S&P 500 was a good proxy for the US economy for much of the last 120 years,” and—save the pandemic—has been a particularly good one in recent years (a correlation of 0.5 or greater is typically considered solid):

And, given that stock prices indicate investors’ expectations about future economic conditions and corporate earnings, substantial declines/increases in the stock market tend to precede big increases/declines in the unemployment rate.

In short, what happens on “Wall Street” is usually a decent sign of what’s been happening—or what’s about to happen—on Main Street, too.

Summing It All Up

Publicly traded companies, big and small, employ millions of Americans and operate in practically every corner of the U.S. economy. When their stocks crater, it affects not only the firms at issue, but the tens of millions of other Americans whose livelihoods and futures depend, at least in part, on “Wall Street” doing well. And that cratering, along with similar currency or bond moves, can both reflect—and sometimes harm—economic conditions in the real world, including for Americans without any direct market exposure.

It’s not just ones and zeroes, after all.

There is, of course, a strong motivation for fans of Trump and his tariffs—the clear causes of recent market distress—to pretend both that their preferred policy/politician is harmless and that there wasn’t any real harm to begin with (quite the two-step, isn’t it?). As usual with this stuff, there’s a nugget of truth buried in such claims, but it hides the bigger, more fundamental truth that’s staring us all in the face: millions of people, including the folks paid big bucks to dig through troves of information and try to estimate the nation’s future economic health, think the tariffs and related chaos will be bad for many real American companies, their workers and customers, and the U.S. economy more broadly. It’s therefore nonsense to claim that the last two months of market trouble—and the trillions in wealth that went poof in the process—doesn’t matter. It almost certainly does. And I’m pretty sure at least some of the economists and Wall Street veterans in the Trump administration know that, too.

Chart(s) of the Week

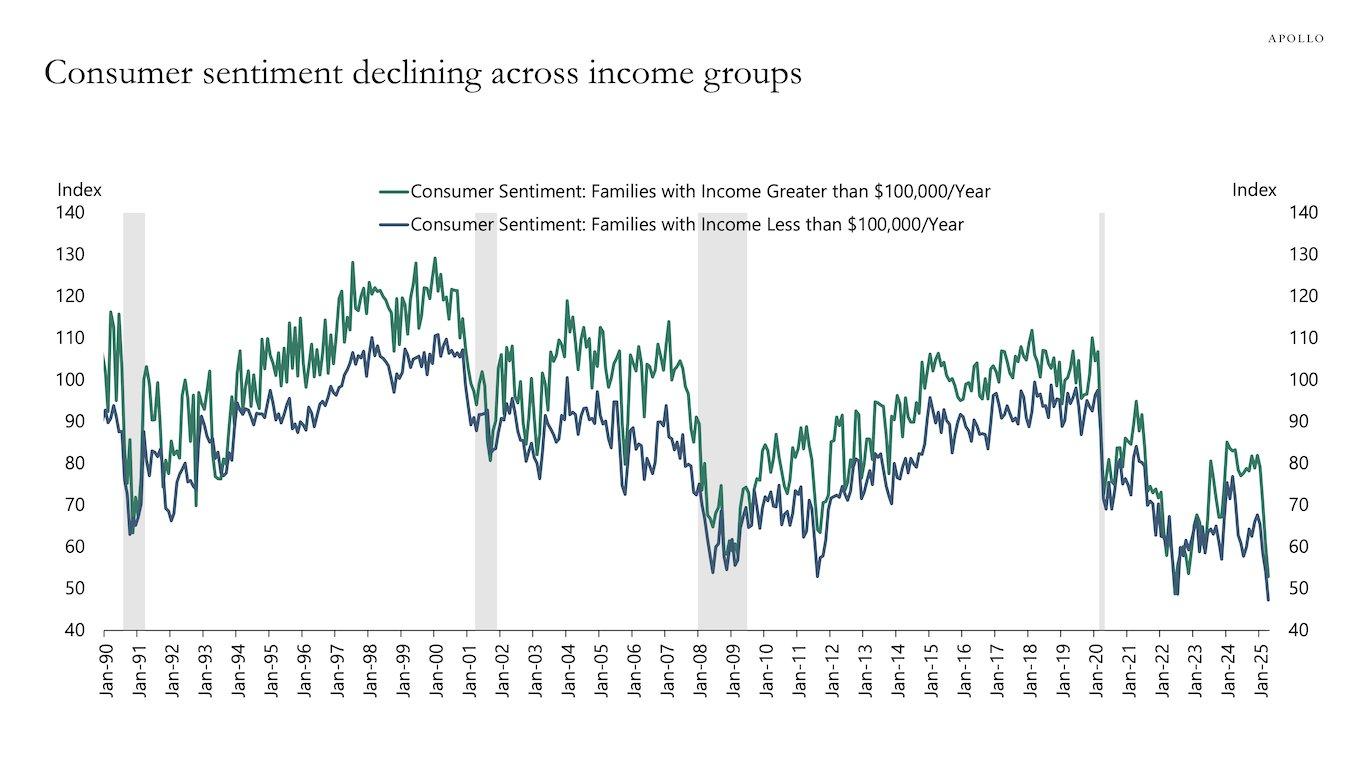

Americans are not psyched right now (and, yes, tariffs are at least partly to blame):