Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

Aspects of artificial intelligence have been absolutely delightful, even astonishing. We have a greater number of facts at our fingertips than ever before, plus the best tools out there draw your attention to a vast amount of literature too.

It seems to have happened so suddenly and incredibly. I find myself still adjusting to this new world. No question that it has enhanced my life. I’m developing a habit of Groking every question.

Not every answer is perfect—I’ve spent quite some time arguing with this fake brain on occasion—but it gives the mind a boost in the right direction, providing hints for anyone curious about nearly every topic.

Ten years ago, I would have had an easy time predicting a vastly smarter world to emerge from this technology. It does indeed make me feel smarter. Perhaps the best part of AI is how it has bested and will probably dislodge the multitudes of fake experts out there ensconced in academia, nonprofits, and corporate life.

They have long been paid to be repositories of information. They surely must sense that they have probably been replaced or, at the very least, their primacy in intellectual leadership faces a severe challenge. Consider too that we are just at the beginning of this. The gap between elite knowledge and that which can be known instantly by anyone will shrink ever further.

There are some mighty implications to this. It will surely lead to a restructuring of many industries, among them those that specialize in knowledge dissemination.

I think back to what we know about Saint Isidore of Seville from the 7th century, who worked with a large team of scribes to write the “Etymologiae.” It was an attempt to record all known knowledge, the first real encyclopedia. It was a project that consumed his life and that of the entire monastery too.

The ambition to accumulate, assemble, and disseminate the corpus of human knowledge has been a driving ambition of many literary projects.

After printing became more affordable and paper too, the market for home libraries opened up in the United States in the 1890s and following. Once the province of the rich only, it became the dream of many middle-class families to have large libraries.

Publishers were ready to accommodate the demand. In 1917, the “World Book” encyclopedia was published. An industry was born with door-to-door sales and subscription services. Countless other publishers got involved in the great task of beefing up the American knowledge base. It was a major part of the Progressive agenda, a means of lifting up the population, educating people in higher things, promoting literacy, and civilized living.

Americans were all in, and books were arriving by mail on a constant basis. Particularly attractive were these large multi-volume sets, not just encyclopedias but novels, speeches, presidential papers, extensive histories, and, of course, the Great Books. Even now, these books are wonderful and form the basis of a great education. You can buy sets of them on eBay for very low prices.

When the Internet came along, the highest hope was that it would become the modern equivalent of all human knowledge. My father was a skeptic. Early on, I showed him some nice new tools, and he instantly outsmarted them with his highly specialized knowledge on a range of particular topics. He did that to demonstrate to me that while these tools can be valuable, they will never be a replacement for serious intellectual work, research, mental discipline, focus, and rich understanding.

At the time, I thought he was just being old-fashioned. But here we are, a quarter-century following the mass distribution of knowledge via the Internet through every imaginable portal, and we have to ask a fundamental question. Are we, as a culture, nation, and world, smarter now than we were 25 years ago?

There are many ways to answer the question. Yes, we have more access, but that has also reduced the incentive to learn and recall. This feature acts in insidious ways. For example, I have an absolutely awful sense of direction. It’s debilitating. In a new city, I’m hopeless. The advent of GPS completely changed my life, freeing me from a lifetime of direction anxiety and enabling me to move about like a normal person.

That said, GPS has absolutely made my sense of direction even worse. Without it, I’m more hopeless than I was in the past. This is how it works. The more dependent we are on external sources of information, the less training we give our own brains to find the answers on our own.

It is precisely for this reason that I suspect the Internet in general has not made us smarter but, in many ways, just the opposite. It gives us more data but drains us of the need to learn how to find information on our own.

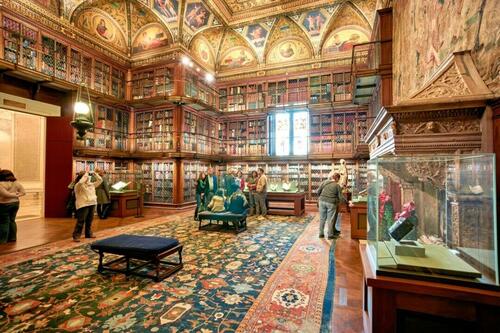

It’s strange how much I treasure those days long ago when I would spend endless hours, day after day, in an old-fashioned library, digging through the stacks, discovering new ideas, reading incessantly on history, philosophy, theology, economics, or anything else I could find. I felt overwhelmed and thrilled at the information and ideas at my fingertips and devoured as much as I could in the time I had.

Do people feel that or experience that today? I’m not so sure. I often read of professors who despair at even getting their students to read a single book. They have invented all sorts of clever tricks to incentivize them and test them to make sure they are not using shortcuts. It seems almost futile.

Is this the world that the Internet was supposed to build? Not really. It reminds me of how the early cheerleaders for television predicted that most of the programming would consist of college professors giving lectures since they believed that would be what the market demanded.

Leading communication scholar Wilbur Schramm said in 1964: “Television can bring education to the doorstep of every home, and it can do so with a power and vividness no textbook can match.”

The opposite happened, and very quickly.

If you want to know how young people use their smartphones, look over the shoulder of anyone under 30 at train stations or airports. You will see despairing scrolling through popular apps that offer absolutely nothing by way of higher edification or education. Really, it’s a disaster.

Explain that to a member of this cohort, and they will respond with some version of: Why should I learn things that are readily available to me if the need ever arises?

It is precisely this attitude that has made us much more stupid. You can tell it from the vocabulary of podcasters and other commentators on the Internet today. Even 30 years ago, whatever language they spoke would not be recognized as English. Something else has replaced it. And it is not just in the United States. It is true all over the world. The French language has declined, and so have German and Spanish.

Vocabulary is a telling sign. It reveals what is in our heads, top of mind. If what comes out is pidgin English, that tells you all you need to know about the lack of thought behind the words.

If this is true of television and the Internet, how much more true will it be of AI and Large Language Models? As information storage and retrieval tools, they make all that came before look shabby by comparison. I’ve stopped using any search engines but for specific tasks. In 10 years, I doubt search engines will even hold much market share at all.

I don’t want to leave you despairing. There are ways in which AI is remarkable, and I would never go back. That said, there is genuine reason to worry that this new tool will only accelerate the decline of language, culture, and learning generally.

Such are the paradoxes of technology: sometimes that which is designed to save us actually destroys us.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.

Loading…